-

Overview

Investors have recently been grappling with a rapidly changing environment as COVID-19, inflation and higher interest rates have transformed the landscape. An increasingly fragile geopolitical picture has also emerged, adding another complex layer in which to navigate.

In 2022, it was the Russian invasion of Ukraine that dominated the headlines. In 2023, it was the escalation in conflict between Israel and Hamas. Of course, these conflicts have occurred concurrently with rising tensions in other regions, not least between the US and China and the enduring risk over Taiwan.

This geopolitical fragility has in part been driven by countries becoming more insular, an outcome of passing peak globalisation, rising trade conflicts and, as a consequence of the COVID-19 crisis, the desire to reshore supply chains.

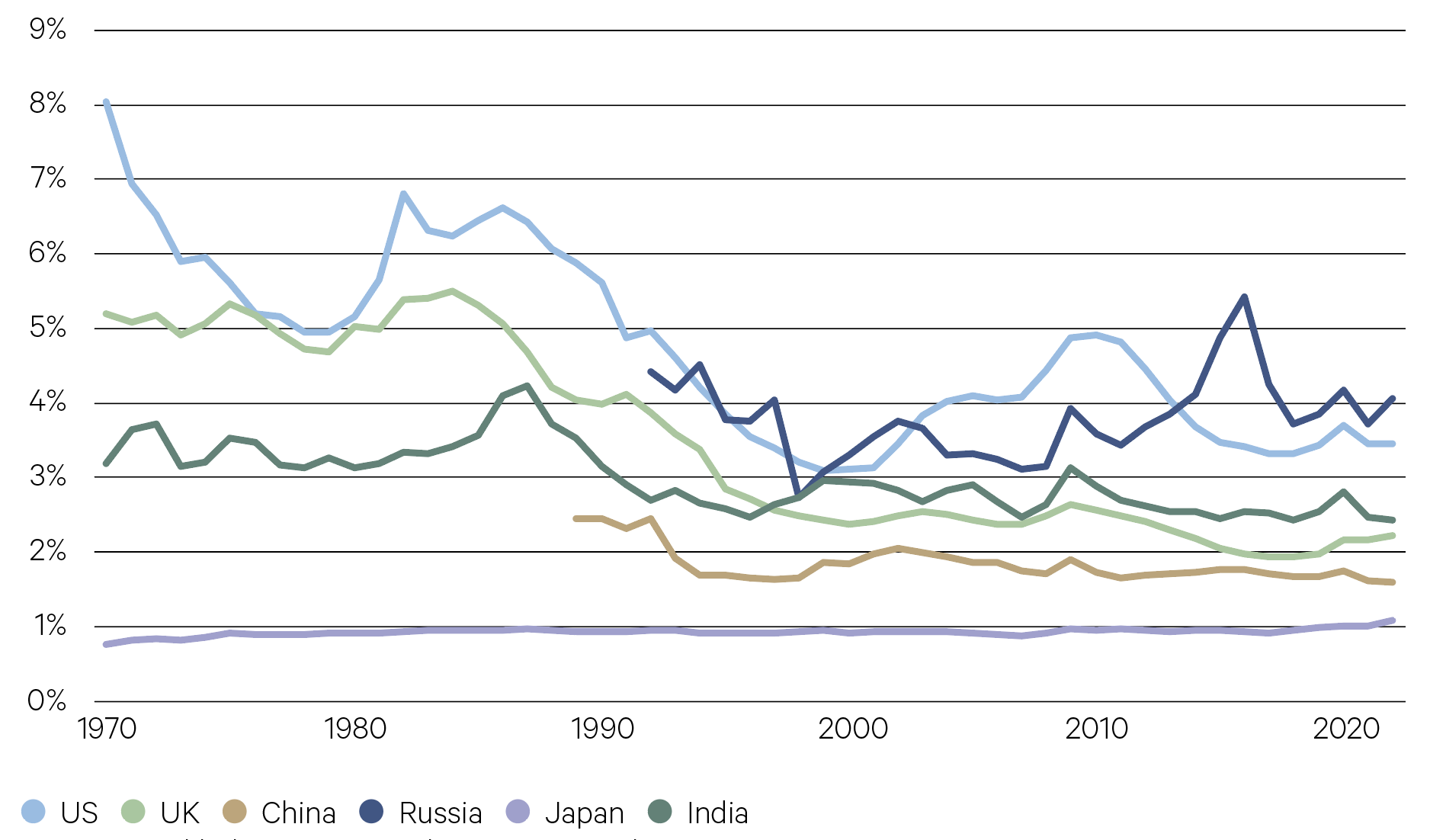

Globally, military spending as a percentage of GDP has declined steadily since the early 1980s and notably since the end of the Cold War in 1991. Military spending was close to 4% at this time, though in the last decade this level has fallen closer to 2%.1 This gave rise to the notion of a ‘peace dividend’ that was realised across the world – the belief that lower government spending on defence freed up resources to be spent on domestic policies, such as health care, education or housing.

1 https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2021/06/military-spending-in-the-post-pandemic-era-clements-gupta-khamidova.htm

—

237,000 – Global fatalities from organised violence in 2022, making it the deadliest year since 1994.

Uppasala Conflict Data Program

—

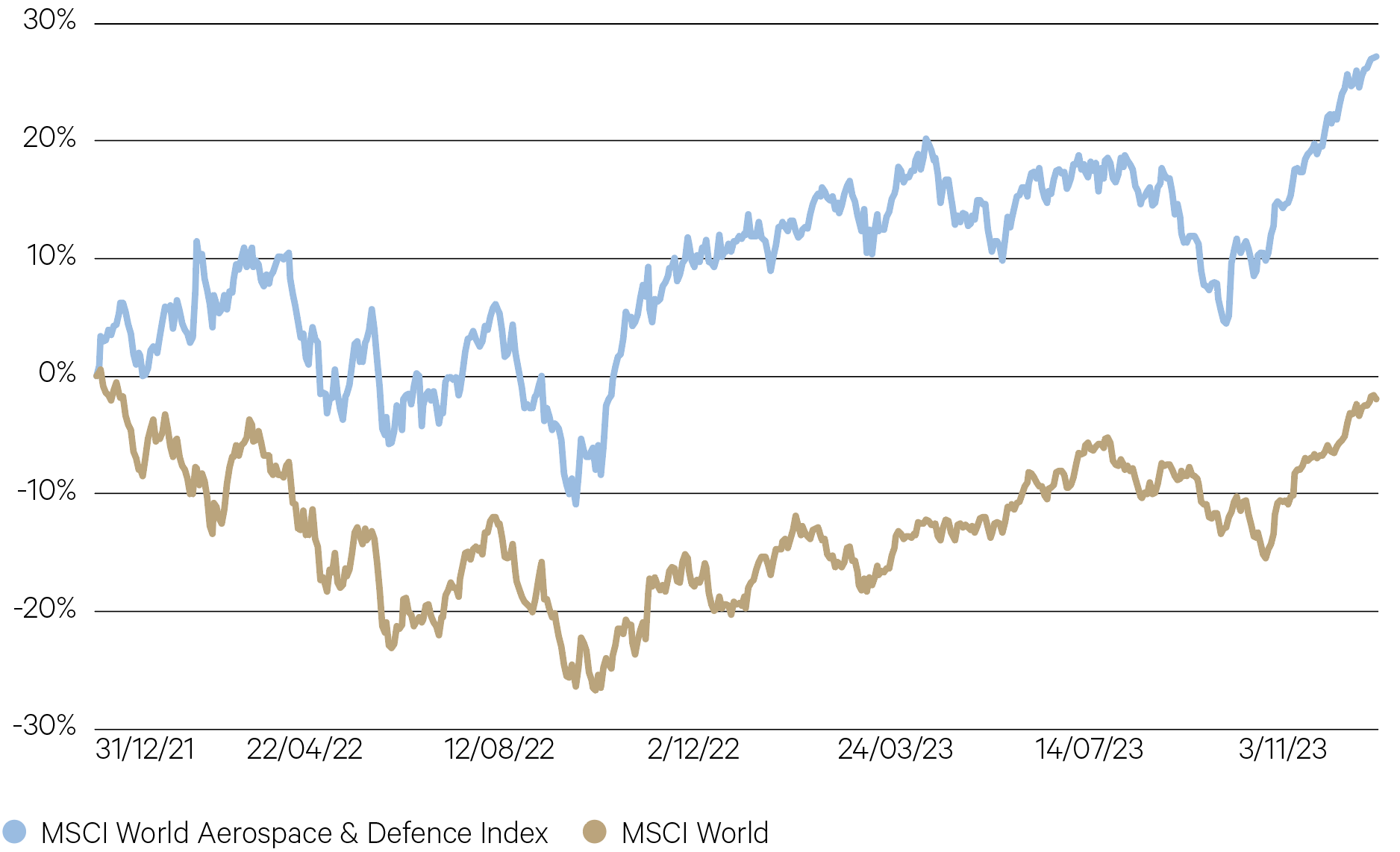

Amid a rise in geopolitical risk and the emergence of significant conflicts, defence stocks have outperformed the broader market by almost 30% in the last two years.

Source: Bloomberg

—

55 – The number of armed conflicts currently.

Journal of Peace Research

—

That prior trend, however, is now under threat. With greater geopolitical uncertainty, it stands to reason that defence spending around the world will rise and become the ‘new normal’. The conflict in Ukraine was a key catalyst, particularly among European countries, to increase budgets. A majority of European NATO members had fallen short of the alliance’s 2% of GDP defence spending target for many years, however the last two years has seen increased commitments from several countries, including Germany, the UK, France and Poland. Other countries around the world, such as Japan, have followed suit.

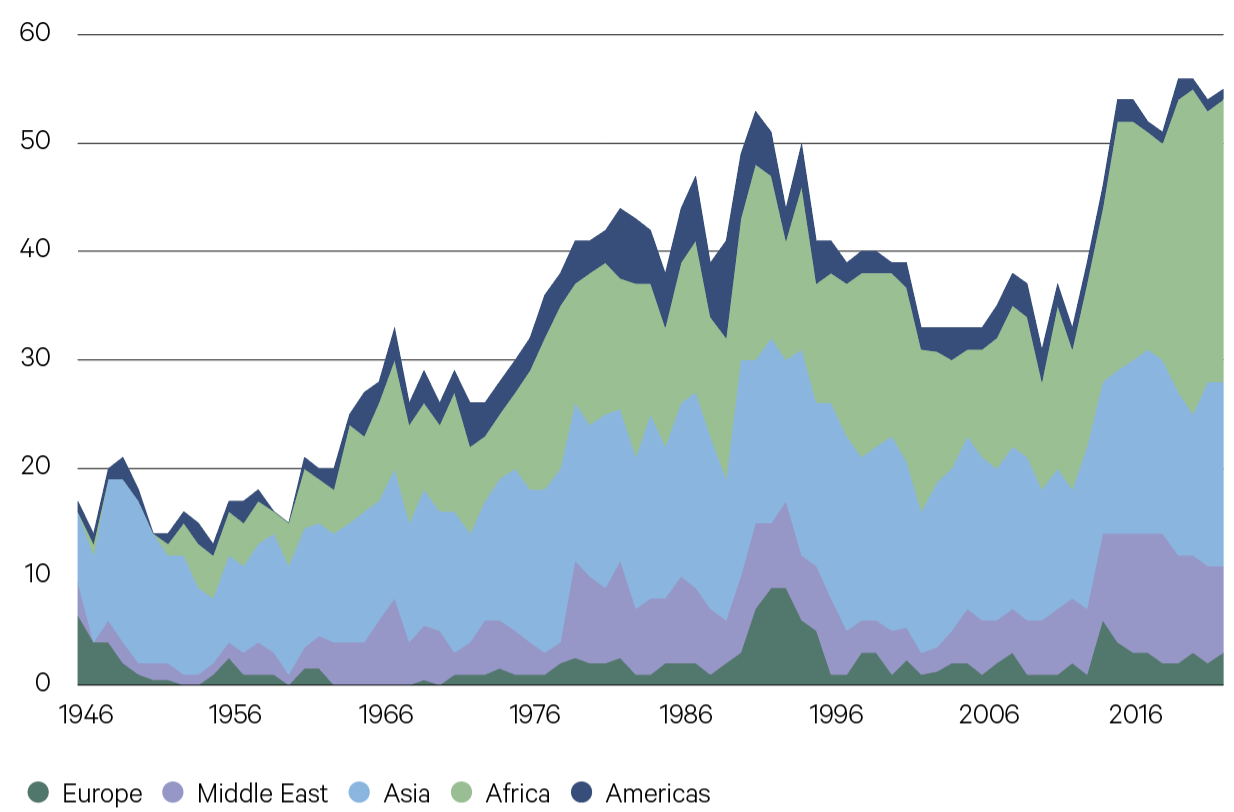

Armed conflicts by region (number)

Source: Davies, Shawn, Therese Pettersson & Magnus Öberg (2023);

Organized violence 1989-2022 and the return of conflicts between states? Journal of Peace Research—

US$874bn – The US defence budget – more than double what it was in 2003 at the time of the war in Iraq.

NDAA FY24

—

Defence spending (% of GDP)

Source: Stockholm International Peace Research Institute

—

The obvious question to arise from these developments is: how will governments pay for this? The options are new taxes or an increase in debt. While the recovery from the Global Financial Crisis ushered in a period of fiscal policy austerity, the post-COVID-19 era is one marked by fiscal policy recklessness; higher government debt levels would thus be the most probable path taken. Making this more problematic is that ultra-low interest rates can no longer be relied on to finance government spending – wars have become more costly for all.

Geopolitical events can rarely be forecast with an adequate degree of accuracy and hence attempts to protect portfolios from drawdowns are often futile. Indeed, these events typically do not have a lasting impact on markets.

There is, however, a myriad of impacts in which investors should consider. Higher debt issuance mean higher interest rates are necessary for investors to lend money to governments. Higher risk-free rates, of course, lift the required rate of return across all asset classes. Additionally, with greater uncertainty comes greater volatility across a multitude of financial indicators, from currencies to interest rates to commodities to equities.