-

Overview

2022 was a year like no other. Shocks ruled and fundamentals and market pricing became a passenger to what were exogenous, unforecastable, events. These events were not in the data and therefore not in the models or minds of investors or policymakers. And yet it was these events that ultimately drove financial market performance through the year.

No wonder economists, analysts and central bankers were so surprised. Coming into 2022, a Bloomberg survey of economists predicted the US economy would grow by 3.9% in 2022 (1.9% is more likely); inflation was expected to come in at 4.3% (more likely to come in around 6.5%); and the official interest rate was expected to be at 0.75% (it actually finished the year at 4.5%).

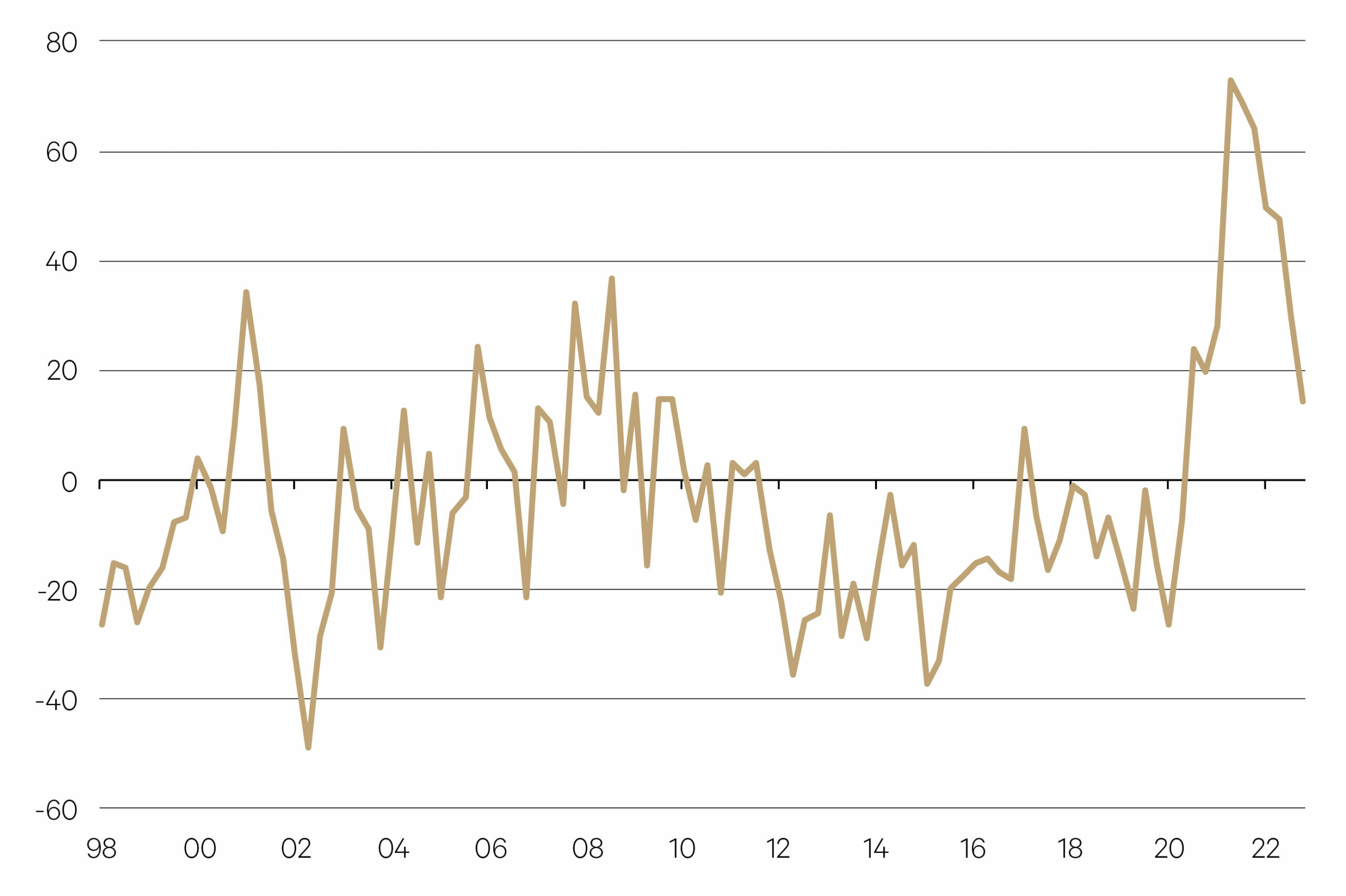

Citi US inflation surprise index

Source: Bloomberg

—

12% The share of the world’s semiconductors made by the US in 2022 compared to 37% made by the US in the 1990s.

—

Shocks to economic, political, health and social systems have been pronounced and their after-effects are likely to be felt for some time.

Behaviour is already changing. Workers are re-thinking their relationship with their employers. Consumers are becoming more conscious of their impact on the planet. Companies are re-structuring supply chains. Governments are investing in new security measures to protect against critical resources such as food, energy, pharmaceuticals, rare earths and data.Global resource allocation is no longer premised solely on comparative advantage. Manufacturing is re-shoring and global trade is declining. When was the last time we had a multilateral free trade agreement? The Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) was never ratified due to the withdrawal of the United States in 2017 (it did evolve into a watered-down agreement which was ratified by the remaining 11 countries in 2018). Resilience, security and national interest are now challenging efficiency! David Ricardo would be shocked.

—

A costlier, more uncertain world

The world has taken a step away from a primary economic objective of efficient resource allocation. There are now multiple, sometimes conflicting, objectives. National interest is driving a rapid rise in fiscal spending on defence, food, energy, and data security. Any one of these could be the source of the next geopolitical event. For this reason, while we do believe fundamentals will play a greater role in 2023 than they did in 2022, geopolitical tensions will remain elevated for some time. This means uncertainty, whilst always and everywhere a feature of investing, seems to have taken a step up.

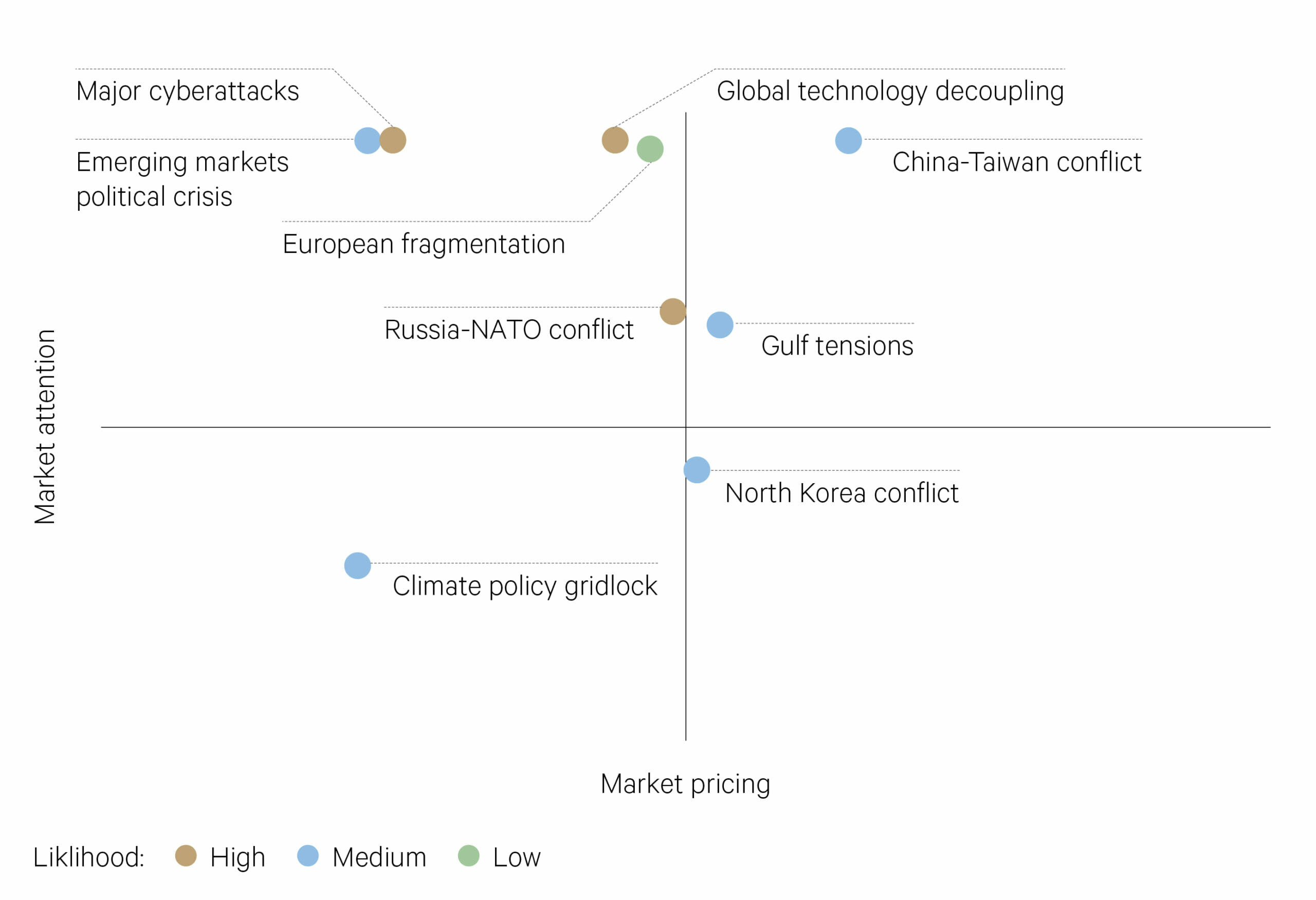

BlackRock geopolitical risk map

Source: BlackRock

—

Anytime there is a move away from efficient resource allocation, costs rise. This doesn’t necessarily translate into inflation if it is just a one-off. Buying protection software against cyberattacks for your computer is a one-off cost. It won’t add to inflation but it will mean an allocation of precious resource that will not add to your productivity. Higher government spending on security measures will have a similar impact on productivity.

Shifting your manufacturing base onshore in the name of security of supply chain will add to inflation because labour costs will be higher. This new, more uncertain, environment has the potential to lower growth in the economy (by reducing productivity) while at the same time adding to inflation pressure.

—

Fundamentals will likely start to matter more in 2023

Some of the exogenous events that we experienced in the past few years are now in the data. The impact of the invasion of Ukraine is in the commodity price data; the impact of covid on the supply of labour is in the wages data; the impact of climate change is making its way into the risk data for insurance companies (and subsequently insurance premiums).

We now know inflation isn’t transitory. This understanding will make its way into company earnings reports and ultimately be reflected in stock prices. Until now, company earnings have largely been impervious to higher interest rates and higher inflation. This is largely because consumers have been cushioned by relief-swollen savings accounts. That won’t continue. Those accounts are running down. Consumer sensitivity to prices will increase this year and this will be reflected in lower corporate earnings.

Money now has a cost and scarcity rather than abundance. There is now a cost to pay for future profitability. A return to focusing on cashflows and fundamentals will necessarily feature heavily this year. Focussing on companies with a high return on invested capital and avoiding those that don’t will be key, regardless of size or style.

–

US$580bn – The amount raised for climate-friendly projects in 2022, more than that for fossil fuel projects.

–

Shock proof portfolios

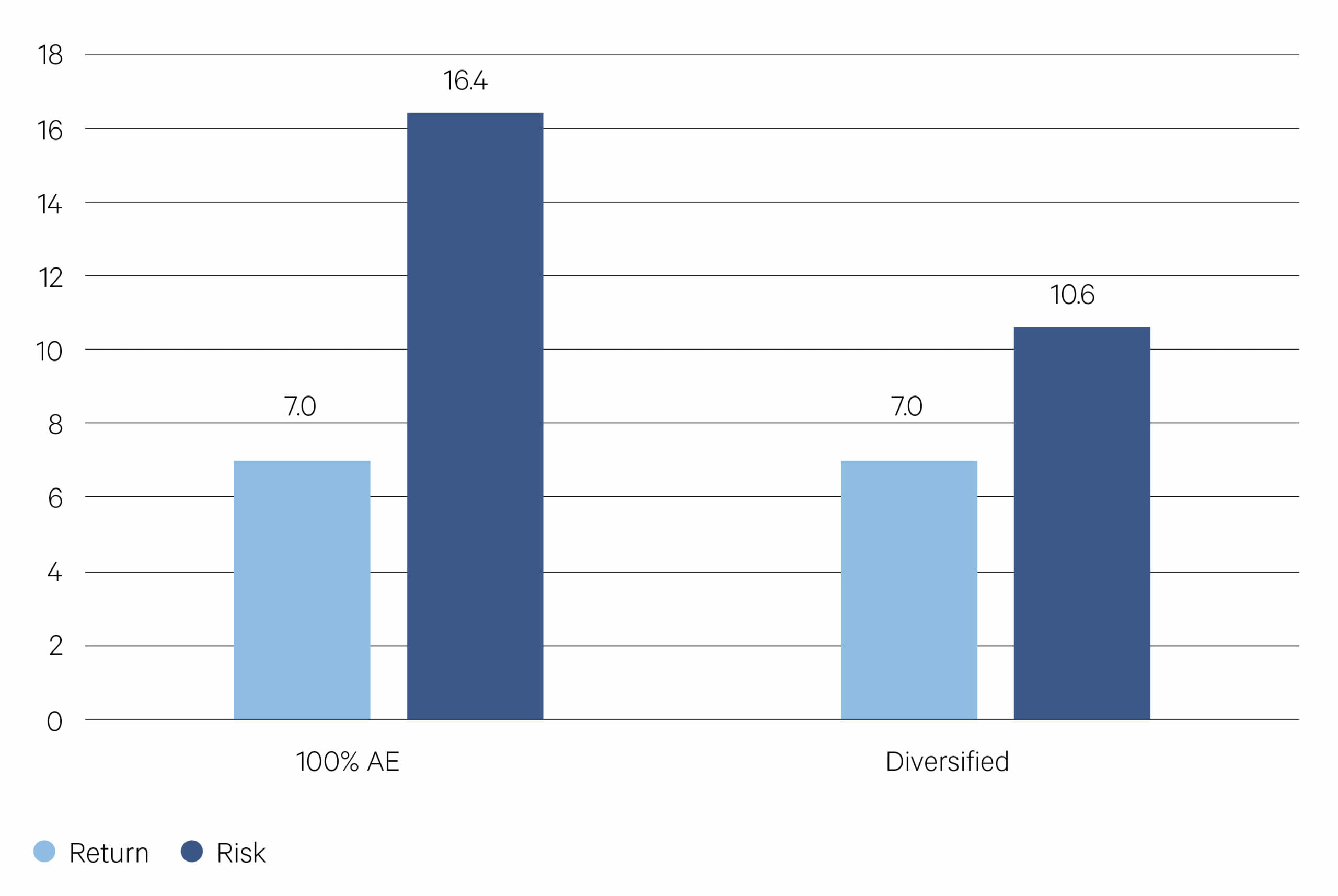

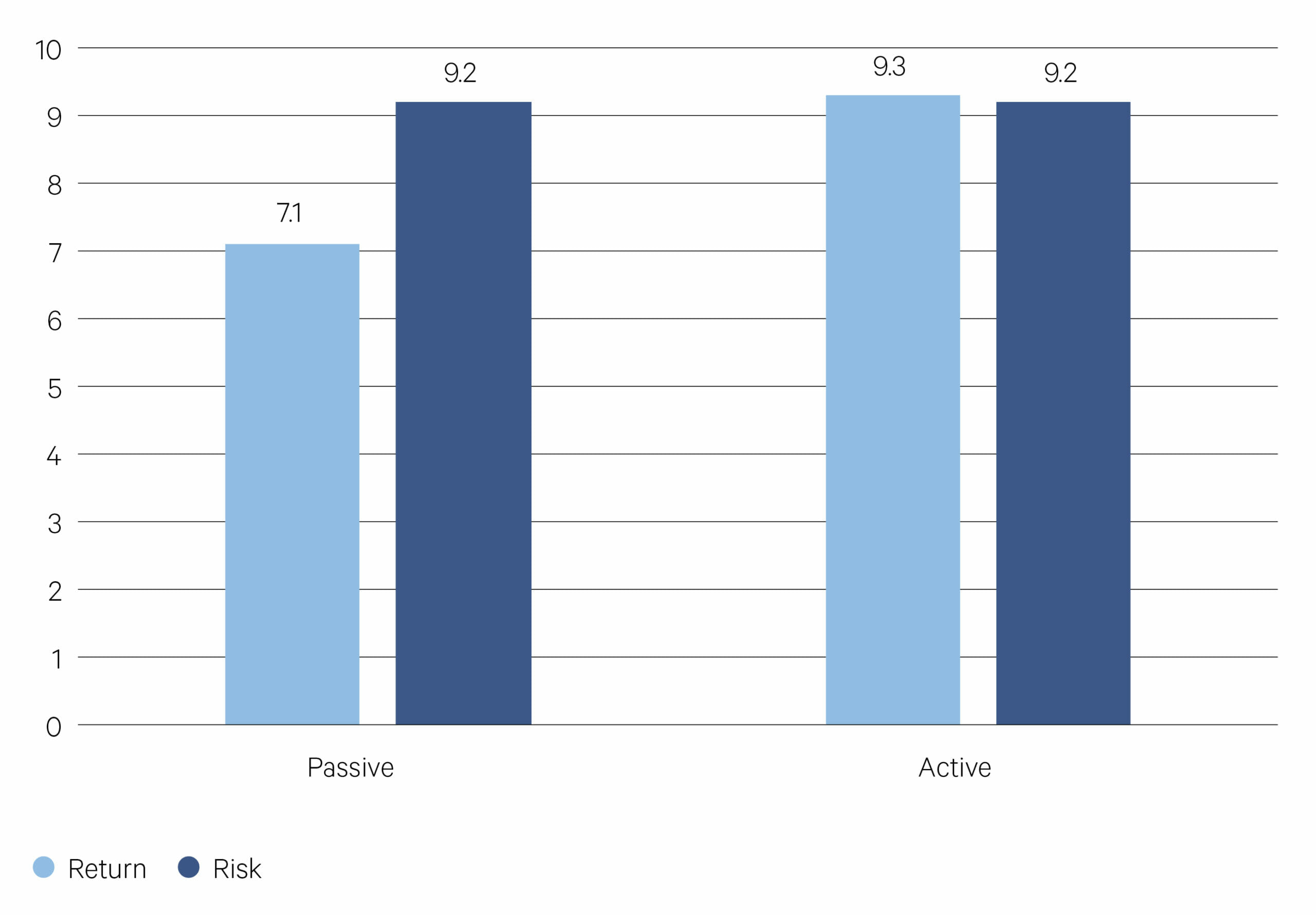

Risk can be priced into an asset price; uncertainty cannot. In the case of risk, the outcome is unknown, but the probability distribution governing that outcome is known. Investors can manage this by understanding how much risk they are willing to take given those probabilities. Uncertainty, on the other hand, is characterised by both an unknown outcome and an unknown probability distribution. For this reason, uncertainty is harder to price in the market. Investors can counter this by building shock-proof portfolios. This means having as many different levers embedded in the portfolio as possible – diversify by asset class, geography, size, and style. The charts below are based on actual performance over the past 5 years.

The charts show that having a diversified portfolio reduces risk (relative to a portfolio that is 100% Australian equities) and having a portfolio of active funds increases returns compared to the passive equivalent.

Less risk being diversified (5yr)

Source: Morningstar, data as at 31/12/22

—

More return being active (5yr)

Source: Morningstar, data as at 31/12/22