-

Overview

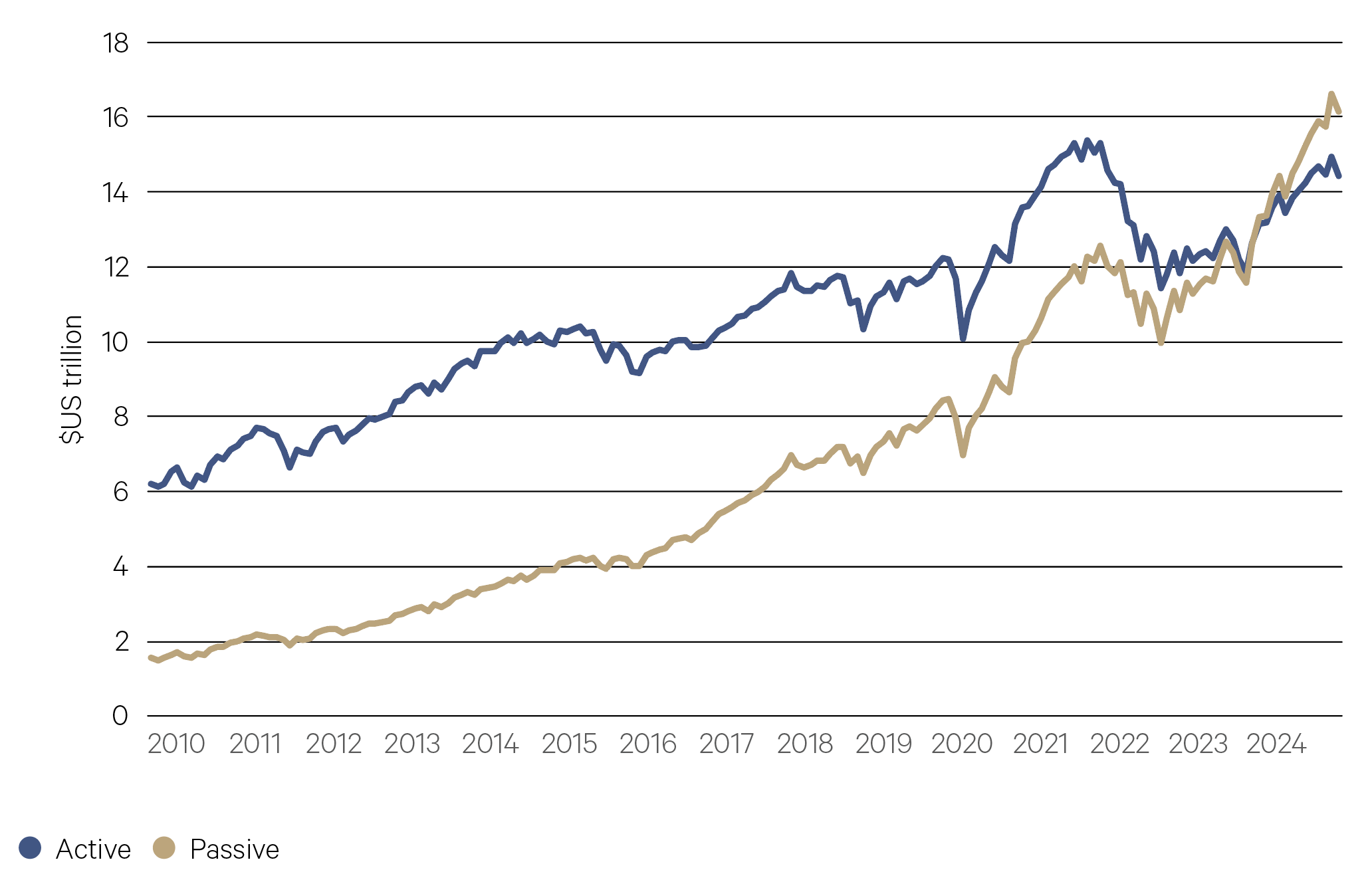

Early last year, Morningstar proclaimed a seismic moment in the US funds management industry; passive assets had overtaken active assets for the first time.

Passive funds align their portfolio weights with benchmark indices. Active managers analyse fundamental data and aim to outperform an index. Passive investing was popularised by John Bogle of Vanguard in the 1970s and have steadily taken market share from active since; passive’s rise is not a fad but a long-established trend that has been helped by the structural decline in interest rates.

US active and passive assets

Source: Morningstar

—

US active and passive assets

Source: Morningstar

—

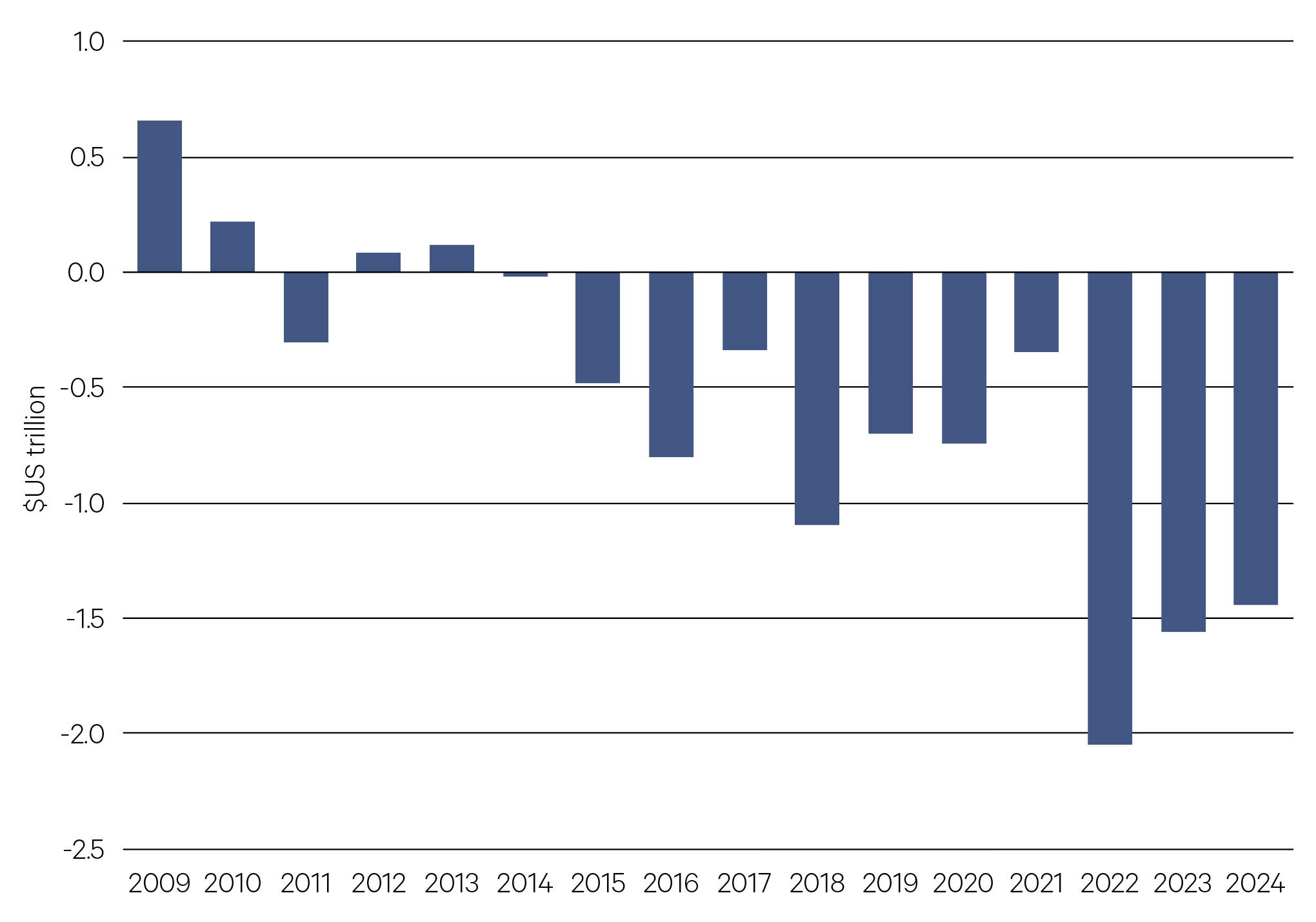

US$9 trillion – Passive fund flows have outpaced active funds by more than US$9 trillion in the last decade alone.

Morningstar

—

Understanding the appeal of passive funds is clear: passive funds have lower fees, as they do not need to cover the cost of expensive research teams. This leads to a critical inference – net of their higher fees, the average active fund does worse than passive. While that’s not to say that individual funds cannot produce strong alpha, the aggregate active industry is a zero sum game with the winners subsidised by the losers. Institutional investors are also embracing a higher passive allocation given its advantages with respect to implementing tactical calls and for improving liquidity.

The rise in passive leads to implications for the investment landscape.

Firstly, passive funds ‘buy and hold’ securities and hence an increase of passive money in the market inevitably leads to reduced liquidity.

—

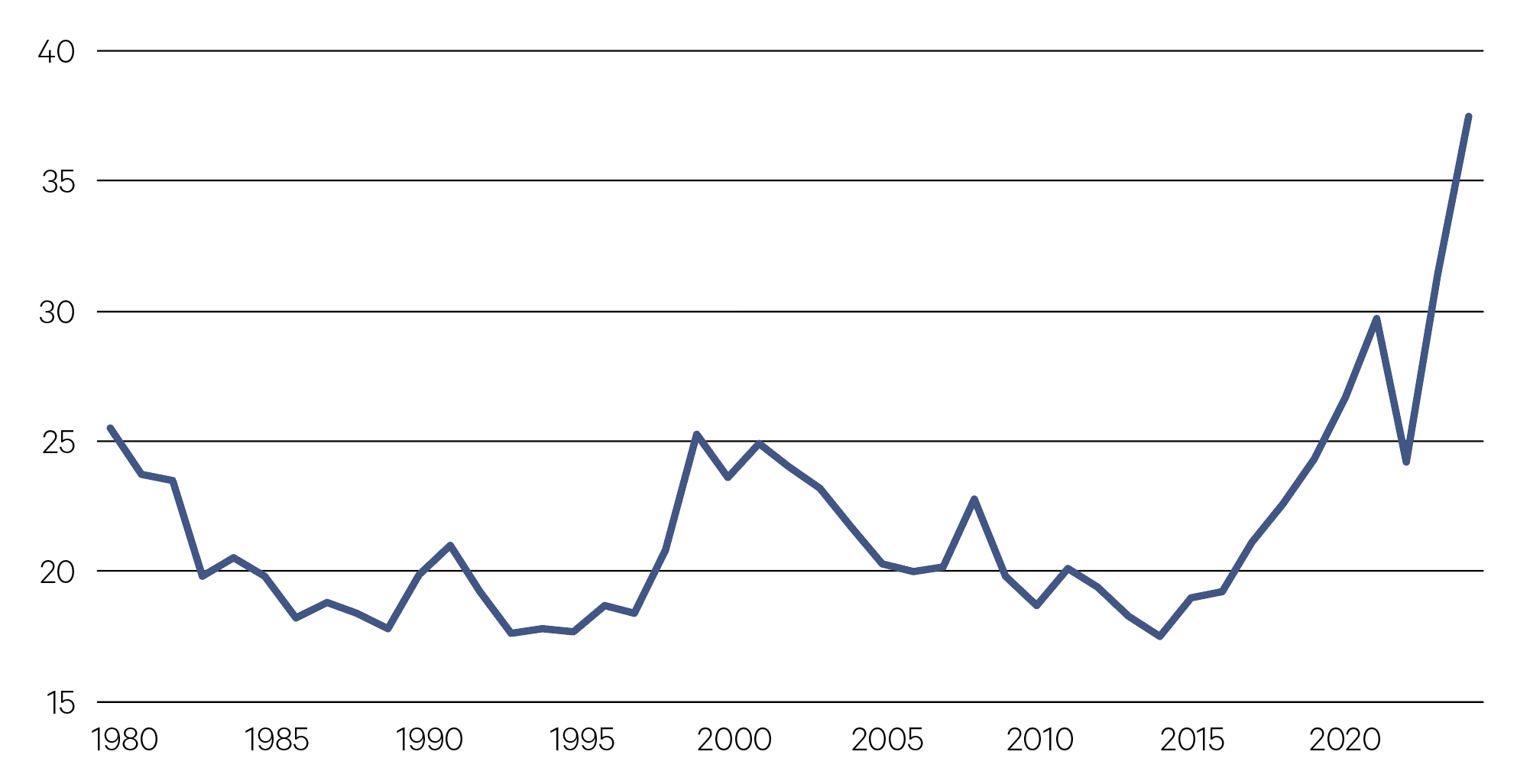

37.5% – The concentration of the top 10 stocks in the S&P 500, higher than any year since 1980.

S&P

—

Passive funds are price takers and don’t trade on changing fundamentals. Many passive index funds and ETFs (Exchange-Traded Funds) are capitalisation-weighted. This means, the higher a stock price moves, the higher its weight in a passive fund. This creates a feedback loop where rising prices lead to a higher weight in the index, which can further attract investment due to the perceived strength of these stocks. In a passive world, the market trades on momentum, not fundamentals.

As large caps are typically the core allocation of a passive investor, this can disproportionately support the prices of larger companies at the expense of the smaller end of the market. The rise of the ‘Magnificent 7’ is a case in point. While superior earnings growth has undeniably been the primary driver of their outperformance of the residual S&P 493, valuation-conscious active funds have been underweight the group as they have soared to new highs. With money flowing out of weaker active funds into passive, this has pushed the Magnificent 7 higher, creating further headwinds for active funds.

S&P 500: Concentration of top 10 members

Source: S&P

—

If everybody indexed, the only word you could use is chaos, catastrophe.

Jack Bogle, founder of Vanguard

—

A more unstable, uncertain macro environment, such as the one we are likely to be in for the next few years, is one in which active funds should prosper. Individual stocks will be driven by idiosyncratic factors that only active investors can position for. This is the active investor advantage.

Related to this is an end to the structural decline in bond yields. We expect to move into a higher for longer yield environment. As a starting point on which different risk premiums are added, higher bond yields are associated with higher returns. A higher for longer environment will relieve the pressure on after-fee returns that initially drove the market toward passive investing.

While we are clearly not there yet, there is a natural limit to the proportion of the market that passive can attain. As Bogle himself noted, if everyone indexed then ‘markets would fail’. This notion of ‘peak passive’ has been generating increasing attention and at some future point an equilibrium will be realised.