-

Summary

In this edition of our Asset Allocation we will focus on the determinants of valuation within each asset class.

-

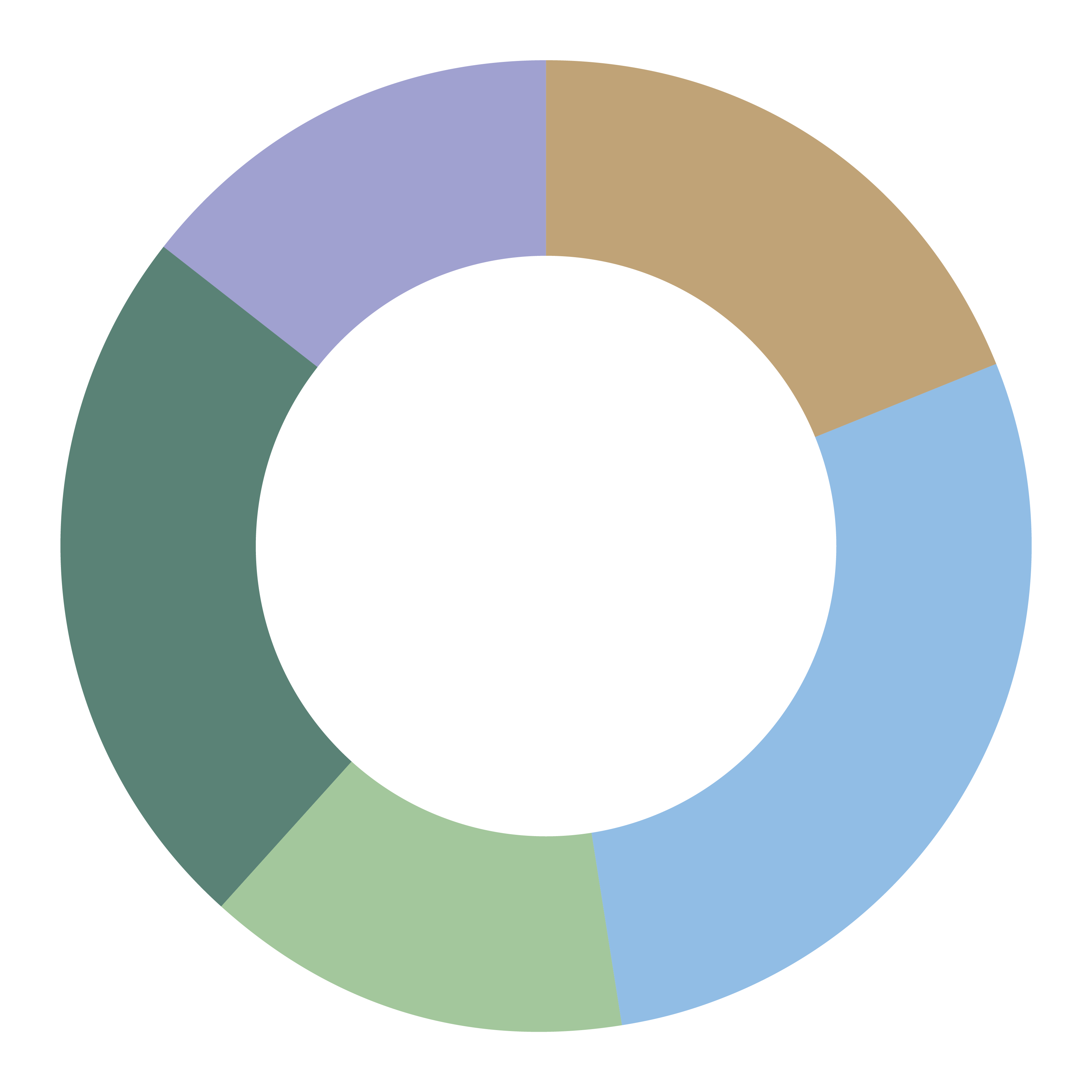

Asset allocation recommendations

Recent data suggests that global growth is faltering but we believe this is a temporary development. Nonetheless the upside may be limited by growing uncertainty on policies such as trade. Inflation remains a key watchpoint as financial markets are likely to react sharply to unexpected trends.

The pattern in global equity performance becomes more correlated as volatility rises. We recommend less focus on the regional weight but rather on the investment style. Portfolios can be designed to provide each investor with a required outcome through the selection and weighting of particular managed funds.

The ASX200 has proven its worth as a value-oriented index. The dividend yield supports a high weight for income investors, yet the growth component is small and relatively expensive compared to global equivalents.

Fixed income remains challenging with both incrementally higher rates and spread widening potentially eroding the coupon returns. Selected domestic debt and global funds can provide satisfactory returns, though there may be some notable short term movements in the capital price. We await clarity on the trajectory of rates before committing to a higher allocation to this asset class.

Alternative asset strategies can form an important component to achieve an investor’s goals. For example, the weighting can be applied to income oriented unlisted property or to low volatility market neutral funds.

Recommended cash weights have been increased in a capital preservation allocation given the narrow options in fixed income.

-

Asset allocation and expected returns

While equity valuations are now less stretched than earlier this year, rising interest rates and sector specific factors indicate that P/E expansion is increasingly less likely. We recommend discipline in equity weight to avoid the risk of an unexpected sell-off as the recent experience demonstrates that investor sentiment is reactionary.

Capital growth is biased to global equity given the concentration of companies that can expand within new industry structures. The AUD is within its fair value range, though unhedged exposures provide some protection in downturns

Fixed income weights have been reduced in capital preservation portfolios. Income oriented investors are encouraged to put aside capital volatility as long as the total return to maturity matches the required outcome.

Alternative investment returns are aligned with risk within each fund manager; higher returns can be expected to be accompanied with higher volatility pointing to the distinctive role that these investments fulfil within a portfolio.

Asset Allocation

Expected index return (excluding alpha and franking)

Expected return (including alpha and franking)

-

Economic Outlook

While some data have been patchy, the general tone of economic momentum remains in place. Regionally, the US started the year at a slow pace, but growth is expected to accelerate through the coming quarters, particularly in investment spending. Europe and Japan have shown a moderating rate of growth in recent months, but still well in positive territory. The rise in their respective exchange rates and structural shortages have been notable features. Emerging economies are generally on a solid path, supported by the global nature of the cycle, commodity prices and domestic consumer trends.

PMI (Purchasing Manufacturing Index) is the primary measure for the business sector given the breadth of the survey encompassing order flow, supply chains, inventory, employment and pricing. Any reading above 50 indicates expansion.

Final Manufacturing PMIs

Source: ISM, IHSM, CXN/IHSM/Have

A supportive factor is the potential uplift in business investment. This is likely to focus on productivity and new systems rather than traditional capacity. The services sector has been resilient to cyclical swings with tourism, education and health all capable of enhancing their quality and quantity. Government spending, however, is likely to be constrained by debt levels, while developed country consumers are also facing limitations on their spending patterns, given the demographic trends in play (aging populations, high levels of debt, job insecurity).

The debate inevitably centres on downside risks. Trade has featured heavily in recent weeks. The consensus is that as long as this issue is contained to limited product sectors, the headline overstates the practical impact. The risk is clearly that there is an escalation in action leading to insecurity in business investment decisions.

Debt is another cause for some concern. Corporations have taken on higher leverage: unsurprising, given the low cost of debt. If this had been put to expanding capacity or improving competitiveness, it would be less of an issue given the expectations of higher cash flow. However, much has gone into capital management, particularly buybacks in the US, or into leverage, such as in private equity. Interest rate markets are becoming more difficult and corporations may be excessively exposed to refinancing into higher rates and a lower appetite for credit securities absent higher spreads.

US inflation, as a determinant of financial market direction, continues to report below expectations. To be fair, there was little indication prices would move up substantially, but that a combination of some pricing power (especially in labour) and reversion from cyclical factors would take the CPI closer to its historic range. It has been the most notable where factors such as tighter employment conditions, a fall in the exchange rate, and cycling of low healthcare and communication costs pointed to a higher inflation rate than is currently evident. These issues may still be latent in the data.

Arguably, the more important issue for central banks is the lack of wage growth at a time of demand for skilled labour in key sectors. If low inflationary and implicitly, wage expectations are so entrenched that households no longer believe in much of a move, central banks may have to reconsider their goals. This will be particularly the case in the US with sub-4% unemployment, fiscal stimulus and tax cuts where corporations have stated commitments to wage rises.

What is clear is that the consumer is behaving in a restrained manner in most countries. House price excess and therefore housing debt have been a feature in Canada, New Zealand, the Netherlands, Sweden and, of course, Australia. Nonetheless, to date it has been reasonably managed through central bank and regulatory measures. The contribution from the household sector, representing circa 60-70% of GDP, is therefore likely to restrict growth.

China is regularly cited as a risk to global growth. Private sector credit has dominated that discussion and with the central authorities seemingly less tolerant of risky lending, the issue has abated, though it remains to be seen if it will be the case were growth to slow more than expected. The current power base has now shifted its focus towards domestic development, ‘Made in China’ and its high-profile infrastructure developments across Asia and the developing world.

Australian economic conditions have improved somewhat from a low ebb in 2017. It is widely accepted that housing activity will slow, albeit at a moderate pace. State-based investment spending has, however, picked up to fill the gap and non-mining capex is also improving. The weakness in the household sector will limit upside, with relatively high debt and low wage growth restricting spending. A recent fall in the saving rate implies that consumers have been spending above their cash flow, a pattern that cannot persist for long.

The key signals to ascertain the economic outlook centre on PMIs and business confidence surveys, credit markets, inflation and wage data.

– Trend in key indicators – inflation, wages, interest rates – may not provide support for risk assets on both the upside and downside. Stronger data imply tighter monetary policy and a higher risk-free rate: weaker data indicates that economic growth may not deliver to expectations.

-

Asset Class Outlook

GDP growth and investment market returns are lightly correlated on an annual basis. While the trend is similar based on one year forward real GDP growth, it is clear that within each economic cycle there is a high degree of dispersion in the annual equity returns.

Global GDP Growth vs. World Stock Returns, 1970-2017

Source: Vanguard

The correlation between economic growth and equity markets has become higher as economies and investors have become globally linked. For the statistically minded, the R2 has moved from 0.28 in the 1970-1993 period to 0.64 in 1994-2017. This latter period is noted for its high growth, rise in global trade and central bank focus on inflation.

The summation is that even with a relatively robust GDP outlook for this year, this will not eliminate the possibility of weak or negative equity returns.

In the shorter term, investment assets are bounded by the combination of valuation, sentiment and market participants.

Sentiment causes volatility, as investors react to news events and perceived level of certainty. Generally, this is temporal as new news overtakes that of yesterday and resets sentiment. But, with a sequence of unexpected events, investors may become skittish and revert to a conservative stance. Often this is expressed by reducing non-domestic holdings, showing a preference for well-known companies or increasing weight in fixed income/cash. While such phenomena occupy much of the financial media, it rarely is predictive of future returns.

Market participants can have a real impact. The majority of investment assets are held or influenced by large institutional (for example, the Japan Government Pension Plan with USD 1.3tr in assets) and sovereign funds (cumulatively USD 5.7tr in assets). These manage either to a liability (common in Europe and parts of the US), to a peer group (common in Australia) or to a long term real return target. While generally slow moving, they are large and can dominate flows if there is a change in view. We note, for example, that Australia has been out of favour for some time, and the performance of the ASX200 has been weaker than other developed markets, though this factor is clearly not the only cause.

Large asset allocation consultants such as Mercer, AON or Willis Towers Watson can also be influential by shifting their view on or within an asset class. They increasingly offer outsourced models for selected parts of the portfolio, in particular ‘alternatives’, given the complexity in assessing such investments.

As the US dominates the pattern in investment performance as well as much of the fund flow, the attitude of investors in that region is influential. Pension plan assets of S&P 500 companies fell to below 80% of their liabilities post-2007, but have now clawed that back to 86%, with this weighed down by a few notable large companies – General Electric, Lockheed Martin, Exxon Mobil, for example. Further, return assumptions have been falling in line with economic growth. Fully funded pension plans have no vested interest in taking undue risk or volatility and can be expected to rebuild their weight to fixed income when interest rates are considered relatively attractive again.

The chart shows the allocation to fixed income for the largest 50 companies in the S&P 500 and a generic rule on the appropriate allocation based on industry average retirement age. On this basis the majority will lift their fixed income weight by about 10% once the asset class is believed to be offering value. This will become even more the case as the participants in these funds enter the latter years of their working life or enter retirement where the allocation to lower risk assets then rises.

Asset Allocation of US Pension Funds

Source: GSAM

Within equities, so called style factors (momentum, growth, quality, value, minimum volatility) do come in and out of favour depending on investor bias. Another route is via managing a portfolio within a narrow risk boundary, as measured by volatility. This can be referred to as risk parity models, but the principle applies to many institutional investors. The higher volatility in equities since the start of the year may see these investors lighten their equity weight to achieve their volatility target.

The Sharpe ratio (the excess return over the risk-free rate as a ratio of the risk or volatility) is a standard measure to assess a portfolio or managed fund. The higher the better. For the past two years the combination of high returns from equity and fixed income, combined with low volatility, resulted in some of the best Sharpe ratios for a standard 60% equity/40% bond portfolio. Not only are the returns now lower, but the volatility is higher and the correlation between bonds and stocks is less stable than before. How investors react to this less attractive risk-return profile is yet to be seen.

Rolling one-year Sharpe ratio of a hypothetical global 60/40 portfolio, 2012-2018

Source: Blackrock

With the large expansion of ETFs, investors have an easy low-cost path to express a view. The flows into ETFs tend to be driven by momentum; that is, investors buy or sell into a rising/falling market. Typically, redemption of managed funds takes time, or is determined by relative performance and other factors. The behaviour of ETF funds and their investors will be tested in a sharp sell-off, given their growth in assets.

Global weightings to fixed income have inevitably been limited by central bank bond purchases as well as the low return now that rates have bottomed. Within the asset class, however, there can be a meaningful rotation between regional bonds and from bonds to credit.

Additionally, there is greater exposure to non-index fixed income, such as asset and mortgage backed securities or mezzanine and other private sector debt instruments. Price discovery in these investments will be restricted by a lack of trading, which can work in favour of an investor by limiting mark-to-market movement but can also result in illiquidity.

-

Fixed Income

Investment in fixed income remains a challenge, and we maintain an underweight recommendation to this asset class. A flattening of the yield curve and a flight to safe haven investments in light of trade policies have tempered the prospect for higher rates, with the US and Australian 10-year bond yield failing to track above 3%. We look for higher rates and a steeper curve before revisiting the underweight position, particularly when adding to long duration style funds.

Credit valuations are predominately driven by the movement in spreads (premium above the risk-free rate), which have widened this quarter after reaching their tightest levels in 10 years. Like rates, we are cautious on credit, noting risk from further spread widening. While this position is frustrating, we believe value will return but patience is prudent. A 10-year government bond rate above 3.25% in the US and 3% in Australia would spark some interest, as would credit spreads that are more in line with long run averages.

Current and historical yields for selected indices

Source: JPM Asset Management

Following a rise in US yields earlier in the year rates have retraced, and bonds may be under-pricing the Fed’s forward guidance for policy rises. Pricing is factoring in upsets that may change the pathway, which is likely to recalibrate as the Fed gets closer to delivering. The tariff policy has had an impact, despite consensus views that the proposal is unlikely to have long term implications. Pro-growth fiscal stimulus could see the return of inflationary pressures in the US economy. While the recent FOMC meeting indicated some tolerance for an inflation overshoot, the central bank will be reactive as evidence builds up. The Fed delivering on rate hikes and an inflationary uplift should be a catalyst for higher yields and lower bond valuations.

Supply and demand dynamics will also drive valuations. US fiscal spending policies and tax reforms have led to a surge in issuance by the US Treasury as it seeks funding to cover the budget deficit. Supply has outstripped demand on the short end, with T-bill rates rising to the highest level in 10 years as Treasury competes with corporates for short term funding. We note reduced demand from previous buyers of treasuries including:

– US Corporates holding Treasuries in offshore entities. Following the US tax reforms Treasuries held by these corporates are being sold as they repatriate funds.

– The Federal Reserve Bank. The Fed is unwinding its balance sheet, starting with a reduction of $10bn a month and rising to $50bn a month. It is now a net sellers of Treasuries.

– Japanese investors. They are said to own nearly $1.1 trillion in US Treasury bonds, second behind China. Japanese investors have reduced holdings citing concerns of a further rise in yields, USD weakness impacting unhedged positions, and the rising cost of hedges as the basis swap moved out of favour.

– Central banks of other Asian countries including China, Taiwan, Korea, Thailand. Historically, countries with sizeable current account surpluses buy US Treasuries to maintain stability in their own currencies and reflect the currency of global trade. Given global reserves are no longer growing at the same pace, demand has reduced.

With foreign buyers and the Fed retreating from buying treasuries, US mutual funds need to step in to be the marginal buyer. One such investor are pension funds. Research shows that 90% of defined level pensions in the US have increased their funded levels (liability versus assets) last year, with this trend continuing into 2018.

The allocation to fixed income hasn’t kept pace with the increase in pension levels. These funds seek a defensive asset allocation, and fixed income plays a role in reducing portfolio volatility. We expect that these buyers will come in to support valuations and soak up supply, but likely at higher rates, perhaps north of 3% for the 10-year.

In Europe, monetary easing is expected to stop or be reduced by September this year which could be a catalyst for valuation weakness. No rate hikes are expected for at least a year as inflation in the eurozone is likely to remain well below target. This is reflected in bond pricing, offering little reward for extending duration.

Emerging market (EM) sovereign debt is in favour by many bond funds. Higher yields are on offer, complemented by improved fundamentals and contained current account deficits. Currencies may appreciate as real rate differentials continue to favour EM. Diluted exposure here can be picked up from the JP Morgan Global Strategic Bond fund and the Legg Mason Brandywine Global Opportunities Fund.

Emerging Markets: 10-year yield

Source: Garth Friesen

Domestically, the probability of a rate rise by the RBA has been paired back, with 2019 being the consensus time frame. Further, the yield curve has flattened and rates on the long end have failed to keep pace with the US, breaking with the long run trend of higher rates in Australia versus the US. At the short end a rise in BBSW led by offshore moves has resulted in monetary contraction, reducing the need for a rate rise. We agree that rates will remain on hold throughout 2018, with the curve failing to offer value or a reason to add duration.

– Our recommendation is to remain underweight long duration in both domestic and global bond funds. We await better valuations before changing this allocation.

Credit spreads are bouncing off their tightest levels in 10 years. Tight valuations have been justified by the macro environment, company fundamentals, low default rates and a low interest rate and inflationary outlook. However, as spreads tighten there is a diminishing risk premium for taking on company risk in what many are calling ‘late cycle’. As interest rates rise, high levels of leverage and falling interest coverage ratios are a concern; as debt matures companies will need to refund at the higher rates. While this stage may elongate for a while yet, capital appreciation from spread contraction will be limited and returns more likely to align with the ‘yield to maturity’ on a bond. The risks to the downside is that spreads widen even further. We remain cautious on credit.

Like rates, a lot hinges on the supply/demand dynamics of credit markets. The increased supply of treasuries noted above, has impacted corporate issuance as they compete for buyers, pushing up short term funding rates both in the US and Australia (Libor and BBSW). Increased supply in the US has also come from foreign bank borrowings following changes to tax laws (BEAT tax) where it is more economical for foreign bank subsidiaries to issue commercial paper rather than borrow from their parent company. On the other side, long dated new issuance from US corporates is expected to fall as repatriated cash from the tax reforms will be used to fund equity buy backs and capital expenditure as opposed to issuing debt.

Foreign financial and non-financial CP outstanding, $ billion

Source: Federal Reserve, Haver Analytics

Demand for short term corporate debt has declined following money market reforms late last year. Longer dated corporate credit is likely in demand while bond yields are at current levels. However, if bond rates move higher, we would expect a rotation out of credit and into governments as the risk/reward is better and tight spreads are not necessarily compensating investors for the credit risk at this point in the cycle.

Following a period of tight valuations, prices on domestic bank hybrids have weakened as investors absorb fresh supply. While the correction opens value, the Labor party proposal to adjust franking credits will weigh on the market, although this will take some time to come into effect, if at all. To be prudent, we recommend a diversified portfolio of hybrids that mature within 3 years.

In summary, we recommend an underweight allocation to fixed income. Within this, we remain underweight both global and domestic long duration funds, with a cautionary note on credit as higher bond yields may widen credit spreads. We highlight the rise in BBSW, which may benefit term deposits and high grade floating rate notes (and related managers) whilst waiting for better entry points on riskier credit and government bonds. For those with a higher risk tolerance, investment into funds that offer an illiquidity premium on floating rate private debt and ABS deals can benefit from the elevated BBSW and more stable pricing, given illiquid assets are difficult to value.

-

Global Equities

We have noted the relationship between bond yields (risk free rate) and equity valuations. Since the bottoming of 10-year yields in September 2017 this has played out in the substantial underperformance of sectors such as REITs and utilities. Conversely, long dated growth stocks have been solid. A rationale for this outcome would be that bond yields are going up, but so too is economic growth and therefore the earnings potential for companies with links to higher demand.

Regionally, the US has the benefit of the tax cuts, expected to add some 7% to EPS in 2018. Yet other indices that have lagged, particularly Europe, and Japan, which are much more leveraged to economic growth and should have been a beneficiary of this cycle. It appears that investors have preferred emerging market exposure as a proxy for this component.

The first quarter of 2018 shows how hard it can be to call out regional outcomes in the short term. The S&P 500 was noted for its relatively high valuation, yet the sell-off has been triggered by the data breaches across IT companies and US trade barriers, rather than valuation. Similarly, attractive valuations did little to buffer the downside in Europe.

With the retracement on indices, most regional price/earnings multiples are now only slightly above their 10-year median, with only Japan trading below that point. The level of valuation to history can be partly explained by the changing mix within equities, especially the weight attributed to IT, social media and internet companies.

A similar pattern is evident in sector valuations where most are at or near historical levels, except for IT.

Sector multiples based on one year forward (as at 31 March 2018) compared to past 10 years

Source: Datastream, WSJ, GS

Nonetheless, a tone of caution is warranted. The move in credit spreads (see section on fixed income) at a time when US balance sheets are highly leveraged (net debt/EBITDA ex-financials is 1.8X compared to 1.0X five years ago) and the rise in volatility alongside the skittish reaction to economic data suggest the market movers in the investment world are likely to take a conservative stance.

We believe there is merit in a combination of momentum and contrarian positioning across global equities with recent months supporting that position.

The long-term growth momentum theme is invariably focused on IT, disruptors and emerging consumer companies. These are prone to overcrowded trades in portfolios as they are innately appealing and we recommend they do not become the dominant exposure to global equities. The challenge in valuing these stocks is complicated. The length of the growth path, the use of free cash flow, and the realistic long-term margin have no precedent and are mostly based on judgment rather than history. We are willing to acknowledge the unique position that is presented in these companies. Yet fund managers will apply differentiated arguments that may result in varying conclusions, for example, the rate and time horizon at which to apply high growth, the potential for other formats to compete and the capacity to manage and monetise data. The outsized impact such a decision can have on performance relative to the index is a challenge given six of the top 10 companies in the MSCI AWCI Index are in the IT sector, in addition to Amazon, which is in the Consumer Discretionary sector.

The mean valuation of the S&P 500 IT sector (as the prominent proxy for high growth) implies that it is, on aggregate, not particularly stretched. Yet, within the sector there are stocks trading at single-digit multiples where they are viewed as likely to lose their relevance, versus some at infinite multiples given net profit has still to be realised. Each stock will have its own characteristics while there is also a tendency for collective performance given the influence of participants such as ETFs.

S&P 500 Tech sector trailing valuation

Source: State Street Global Advisors, Bloomberg as of March 21, 2018

Outside the WCM SMA portfolio our recommended managers are biased on stocks that have a more traditional valuation bias. These include the assessment of business direction, cash flow and capital management through a cycle, alongside a specific view on why the stock is undervalued.

A wide number of stock selection processes can be applied with different results. The greater the emphasis is on valuation of long term earnings, the less important are shorter term issues and market behaviour. Conversely, a fund manager may focus on stocks undervalued on a near term outlook where the pricing is subject to a bias and a change has not been recognised.

Valuing each stock is therefore subject to several variables that can result in different decisions. Simplistically, one is looking for pattern of success of each fund manager within a given methodology.

Most managers will acknowledge that a hit rate of 55-60% is a good outcome and we can observe this with access to an attribution from each fund. Contribution from other parts of the equation are at least as important as the assessment of the merits of each stock. These include the sizing of positions, the trading to establish or sell holdings and the diversification across regions and sectors to avoid unreasonable levels of concentration.

In summary, valuations of higher growth companies can be supported by their scarcity, the structural changes in industries and their capacity to generate high free cash flow. Yet, it should not be based on a case made without retesting the assumptions to avoid confirmation bias. Stocks that fall into the ‘growth at a reasonable price’ (GARP) or low value segments are an important part of the mix. GARP stocks tend to be stable moderate growth conservative companies whereas value emerges due to investors’ natural aversion to stocks that have experienced some weakness.

– Given the change in interest rates, a debate on the length of economic growth in this cycle, unpredictable regulation and policy measures, we believe this is the time that several investment styles via differentiated managers will matter more. Our recommended managers have been deliberately selected based on a distinctive investment methodology and evidence that they tend to do better than the index in times of drawdown.

– Equity is still the best positioned asset class. The natural call is to state that this bull rally has lasted a long time and therefore due for a pullback. Additionally, the change in interest rates implies that valuations should be reconsidered. But growth is still there, EPS trends are positive and should see leverage to higher revenue from demand. Valuations are, in aggregate, modestly at the higher end of historic ranges, but do not suggest this is the basis of any further retracement.

-

Domestic Equities

The Australian market declined in the first quarter of 2018, broadly in line with international equity markets. With earnings estimates holding up well, the market has de-rated and now presents as better value. While risks have risen in international equities (interest rates/inflation/trade), the Australian market remains less attractive than most based on its valuation (on a comparable sector basis) and average, narrow-based, earnings growth.

Growth and momentum have continued to be the primary factor drivers of returns, while the rally in resources has tapered. Within the Australian market, exposure to higher earnings growth is best expressed through holdings in mid and small cap companies (and in large caps, through funds such as Wavestone) and many of these have posted solid returns this financial year to date. While this has meant that our SMA managers (which have a value/income tilt) have not participated to the full extent in the rally, the valuation argument is currently in their favour. In the following section we discuss the valuation status of the key sectors of the domestic equity market.

Resources

Net Present Value (NPV) is the primary valuation measure for resources companies. NPV captures the net discounted cash flows at the company’s weighted average cost of capital and recognises the fact that resource bodies have a finite life. There are multiple input assumptions that are used in an NPV calculation, including production, commodity prices, operating costs, capital expenditure, financing costs and exchange rates. The most sensitive of these is typically to commodity prices, which are difficult to forecast. A change in commodity assumptions particularly applies to higher cost mining companies that have significant operating leverage. Given the wide range of assumptions used, NPVs are often used as a guide and are useful in answer the question: what the company is worth under a specific scenario.

On an NPV basis, resources stocks would be viewed as fair value based on current forecasts. As noted above, understanding commodity price inputs is key to form a view on the level of conservatism in these valuations. The consensus view is for the prices of several key commodities to gradually decline in the medium term, including iron ore, coking coal and oil. Thus, if the recent commodity recovery of the last two years is sustained for longer than expected, these stocks may reflect better value. A further benchmark valuation technique uses current or spot prices as the commodity price assumption going forward; on this basis there would be considerable upside to the share prices of resources stocks.

On other measures, following the rebound in profitability across resources companies, one year forward multiple valuations are quite attractive. EV/EBITDA is the most widely used in the market and applying a 6-7X forward multiple as a base case would result in the big diversified miners screening as good value.

Banks

The major banks have underperformed the benchmark index materially over the last six months and thus an underweight position in the largest sub-sector of the domestic equity market has proved to be a sound call. Various valuation measures give contrasting views on the present appeal of the sector. On a forward P/E basis, the banks are inexpensive, although this has to be considered in light of a flat earnings growth profile in the medium term. The recent underperformance, coupled with only marginal downgrades to earnings estimates, has led to the P/E discount relative to industrials increasing to the widest level in several years.

The relationship between price to book (P/B) value and return on equity (ROE) is a widely used valuation measure for the banks. As we have noted, P/B has declined somewhat over the last few years, although this can largely be explained by a falling ROE profile due to the additional regulatory capital that the banks are now required to hold (hence they are now less leveraged). This change should thus be viewed as structural in nature. On this measure, the banks can be judged as fair value.

The strongest argument for the banks is due to their yield characteristics. All are trading on a forward dividend yield of 6-7% (and up to 10% at a gross level if franking credits are included). Additionally, their yield premium to the ASX 200 and to fixed income benchmarks also plays into their favour. The current dividends of the major banks are viewed as sustainable as their respective capital ratios now meet APRA’s new regulatory requirements. With credit growth benign, however, little expansion is expected in dividends, with the outlier risk a potential normalisation of bad debts.

A dividend discount model (DDM) is a simple valuation technique that is used to value consistent dividend stocks, such as the banks. Using modest dividend growth assumptions, the banks could justify their position in a portfolio for an income investor, particularly given that high-yield alternative options are typically sensitive to rising interest rates. Potential proposed changes in the taxation treatment of franking credits for some investors could, however, impair this argument.

Industrials

Industrials cover a very broad section of companies and sectors. The price to earnings ratio (P/E) is the most widely used and is a simple and effective measure of value as well as comparing between stocks, particularly in the same sector. P/Es can be forward or backward looking (trailing P/E), and while forward measures are prone to inaccuracy (given how much earnings estimates can change over a 12-month period), they are more useful in assessing value. The limitations of a P/E include the fact that it is based off the earnings of one year (and hence does not capture earnings growth beyond this time) and it does not adjust for the quality of the earnings base or where a company may be in a particular cycle.

We have noted these P/Es have been above average for some time now, although some stocks are now starting to look better value due to the recent share market weakness. The chart below illustrates the P/E of the market (ex-resources) and compares this against the average over the last five (red line) and ten years (black line). Presently, the market is trading at a 10% premium to the 10-year average, but broadly in line with its five-year average (although one needs to be wary of the highly accommodative monetary policy settings in this time). An earnings environment that has been improving, yet limited by the low growth nature of many of the largest stocks in the index, is currently balanced with the prospect of higher interest rates, which should have the effect of reducing P/Es, all things being equal.

ASX 200 (ex Resources) Forward P/E

Source: State Street Global Advisors, Bloomberg as of March 21, 2018

The following chart shows the average P/E of each sector of the market compared to its range over the last ten years, which shows a fairly high level of dispersion. Higher growth sectors (health care is the most notable) trade at a premium to other stocks, however the current premium for growth is noticeably high; health care, information technology and consumer staples (which includes stocks such as Treasury Wine and A2 Milk) are towards the top end of their decade range. While this is not too dissimilar to global equity markets, within the Australian market the premium is even higher, reflecting the growth scarcity factor in the ASX200. At the other end of the scale is telecommunications (largely driven by Telstra), which reflects the difficult earnings environment, while resources and financials screen as fairly good value.

ASX 200: Sector P/Es: Current and 10-Year Range

Source: Bloomberg, Escala Partners

Interest Rate Sensitives

REITs, utilities and infrastructure have been among the big underperformers in the March quarter. We have noted the risks to their valuations (whether it be multiple-based or internal rate of return) from rising interest rates. With the Australian interest rate cycle lagging that of several overseas markets, long bond yields are essentially unchanged since the beginning of the year. While the longer-term risk is one of interest rate normalisation, the selloff in this group of stocks appears to be overdone in the short term.

-

Alternatives/Property

As is the case with other asset classes, property investments require a valuation framework to determine whether a potential investment will meet its intended outcome. The most common metric is the capitalisation rate (cap rate), which is the ratio of net operating income to the property value. This allows for a comparison between similar properties within the same segment of the market.

Investors can be willing to accept higher prices (lower cap rates) if specific factors of a property meet their requirements. Considerations include the condition and location of the property, tenancy profile and the weighted average lease expiry (WALE). This is illustrated in the current dispersion in valuations within the Charter Hall Direct Office fund.

Source: Charter Hall

The properties with lower cap rates will generally have a longer WALE, an attractive tenancy profile or reflect their scarcity.

There are broader supply and demand fundamentals that can drive property valuations such population growth, employment conditions and inventory of comparable space in a sector. Healthcare property has been the beneficiary of Australia’s growing and aging population. In addition, supply has been contained, unlike that of office and residential. Consequently, cap rates have compressed from the 7-9% range a few years ago to 5-7%.

Interest rates and availability of debt also has a significant impact on cap rates. It goes without saying that rates have been very favourable, while the debt market has widened due to the participation of the non-bank sector. There is a preference for debt to be at a property level rather than fund level to avoid unintended impact from any issues that may occur within the portfolio.

In testing the sensitivity to valuation there are three main criteria. Vacancies, interest expense and the cap rate. Typically, vacancy risk is limited by the WALE, the mix and number of tenants and the desirability of the space to alternative tenants. Interest expense comes down to the maturity profile, mix of fixed and floating rates and spread premium that may be need to be paid to gain the required terms.

The key impact, however, will be the cap rate at the time the property is realized or the investor elects to sell a holding. This risk is considered through the nature mix of issues raised above as well as the potential of realizing property assets in an economic downturn. Investors may need to exercise patience in unlisted fund or limited redemption windows to achieve the intended IRR.

Other alternative investments such as market neutral and macro strategies do not lend themselves to a formulistic valuation technique. The majority benchmark against a cash rate reflecting their aim of absolute and uncorrelated returns.

We view the apporpriate measure of their success as the return compared to the risk or volatility in performance. As such, we have noted that this has been as expected, that is, higher returns have only been achieved by higher risk.

Worst 10 months of the ASX200 in the last 5 years vs our preferred Martket Neutral Funds

Source: Morningstar, Escala Partners

The above chart shows that our preferred Australian market neutral funds have all outperformed the ASX200 during its worst 10 months in the last five years by an average of 5%. This further demonstrates the volatility dampening role that market neutral funds have within a client’s portfolio.