-

Summary

Formalise the asset allocation framework

The intention of asset allocation is to provide a framework for an investor to consider the rate of return a portfolio can achieve and, most importantly, the potential volatility and risk in those returns.

Asset allocation will determine the volatility of portfolio returns

Studies of investment markets demonstrate that asset allocation is likely to be as important a decision as the holdings within each asset class. Some investors may be aware of the oft quoted suggestion that asset allocation will determine most of the portfolio returns, whereas it is rather the volatility of returns which is a function of the asset mix.

Initial date of an investment matters

The methodology behind asset allocation depends on data derived from observed trends in asset classes. The time frame and starting point of any set of data can have a meaningful influence on the interpretation of performance and we encourage investors to understand what the fundamental influences were which caused performance.

Expected returns are stated within a range of likely variation

Forecast returns and volatility are based on a combination of historic experience, valuation of asset classes at any point in time and economic circumstances expected to rule under the forecast period. While some report precise return forecasts, we stress that returns should be viewed within a range. This is captured by the risk metric, or standard deviation.

The priority of a portfolio is critical and trade off recognized

Investment requires some compromises and trade off or ranking in priorities. In our opinion, this is why investors are well served by individual asset allocation decisions as this allows the portfolio to reflect the aims of the specific investor. Our recommendations should therefore be the framework for discussion rather than the final conclusion.

In this report we consider some of the aspects important to asset allocation, such as the determinants behind the weight to growth versus income, the role of each asset class and the nature and pitfalls of benchmarks commonly used. We start the note with a check list.

In our regular quarterly asset allocation reports we provide our specific recommended allocation for various groups of investors.

As always we welcome any feedback and topics for subsequent reports.

-

Eight factor check list

– Asset allocation is investor specific. The purpose of a structure is to provide discipline, to encourage a change in the weighting of asset classes depending on the conditions and to show the likely range of returns that can be achieved.

– Each asset component serves a unique purpose and it is the mix and composition of these assets that creates the portfolio, not each individually. Convention groups assets into indexes and implies each will make a discrete and distinctive impact. In practice, financial assets can be viewed as a continuum of the capital invested in managing goods and services. For example, the risk/return in certain parts of fixed interest markets is akin to equity and conversely some equities can have a correlation to fixed interest.

– The time frame within which the funds are managed is critical. Logically, within a short time horizon, the allocation may be very different compared to a portfolio intended to be invested for the long term.

– The liquidity of each holding should be assessed not only based on the time frame in which it may be realized, but also the behaviour of that asset class in the event of disruption to markets. Having some understanding of who the participants are in the asset segment is essential.

– Typically, the return and volatility of each asset class is based on the performance of a recognized benchmark. The flaws in the structure of benchmarks is a large topic in its own right, yet it remains appropriate to anchor the asset classes to some measure and as long as investors are aware of the deficiencies, benchmarks provide an adequate guide.

– Frequency and timing of investment decisions can influence asset allocation. While it is generally unproductive to attempt to time market participation, there are events which can have a substantial influence on the potential outcome of an investment portfolio.

– Ability and willingness to include all product options. The combination of direct, index funds and managed funds are, in our view, necessary to effectively allocate to all opportunities.

– A trade-off is inevitable and therefore the order of priority must be established. For example, preserving capital, or limiting the risk of capital loss, is likely to compromise the real growth of a portfolio.

-

Determining asset class allocation

The starting base of asset allocation

Traditionally, asset allocation is quite simple. The starting base for an average investor is 60% equity (or growth assets) and 40% bonds (or defensive assets). Typically there is a sliding scale dependent on the age of the investor. Inevitably there is a large number of investment professionals that provide good reason to finesse this split.

Adapted to investor needs…

In our view there are two determinants.

– The first lies within the factors noted in the check list above where specific investor requirements allow for a structural move away from 60/40. The key is that this allocation setting should be decided upon regardless of the historic or expected performance of each asset class, but rather due to its underlying characteristics, such as income, growth or liquidity.

…and accounting for investment conditions.

– The second is to take advantage of changing fundamentals in asset classes. The aim is to add to assets or securities with the best potential performance.

– The chart below shows the ‘optimal’ allocation that should have been applied to a global equity/government bond portfolio to achieve the best excess return, that is, return for the risk taken. In the perfect world, bond allocation should have varied between 0 – 90%, while averaging 43%.

10-year periods, using 1900-2010 annual data, cross-country averages

In the perfect world an investor would only be in one asset class – the one with the best return at any time. In the real world a deviation from a base allocation rests on confidence in the probability of one asset class outperforming another.

Discipline through prescribed asset range bands

Setting a prescribed range of exposure for each asset class is necessary if asset allocation is to play the appropriate role in achieving expected returns.

The key issue is that the allocation is a decision rather than an outcome. Allowing performance alone to determine the weight in an asset class is akin to adding a new dollar to that asset class.

Maintaining a lens on valuation and security selection prevents simply following a well performing asset class by default. The opposite course of action should always be considered; buying what may be cheap and out of favour.

Prescribed bands that limit asset class performance are widely used. For example, if fixed interest accretes in value relative to other assets, it may be sensible to realise incremental amounts above this range, as otherwise it could imbalance the portfolio and leave it vulnerable to changes in interest rates.

Individual decisions should have a distinctive rationale and add to the portfolio structure. Culling holdings where the investment thesis is no longer valid, or has changed, can make a considerable difference to performance.

-

Purpose testing asset segments

Role, risks and opportunities in investment assets

While most investors will be quite familiar with asset classes, it can be useful to reflect on the basic criteria that underpin these assets.

The goal of any asset class is a mix of:

1. preservation of capital;

2. producing stable income; and

3. achieving capital growth.

Noting the goals above we note the some of the security characteristics that can contribute to a portfolio.

Features of asset classes, in order of benefits

Equities

Equity risk is relatively high and is dependent on management decisions as well as external influences

Risks and opportunities:

– Corporate risk – the strategic decisions and execution within each company. The significant divergence in share prices even within similar industry segments is compelling evidence that management play a large role in investment returns;

– Capital and balance sheet – capital management and leverage can independently have a considerable impact on returns;

– Market valuation – the value attributed to equities can vary widely and is rarely predictable; and

High liquidity – equity markets can be influenced by trading programmes and flows which may be unrelated to the merits of the underlying stocks.

Debt securities( fixed interest, floating rate, hybrids and Term Deposits )

Fixed Interest risk is centered on interest rates and possibility of default

Risks and opportunities:

– Interest rates – rising interest rates negatively affect the price of fixed rate securities. The longer the maturity, the greater the potential for capital volatility;

– Credit spread – the spread over government bonds or the bank bill rate will be influenced by the quality of each issuer (which can change at any time) as well as general economic and financial risks;

– Liquidity – the tradable market for fixed interest securities can be shallower than many other financial instruments. In recent times the participants in some parts of the fixed interest sector have been influenced by monetary policy, as well as regulatory requirements. We specifically note that investors in the domestic listed hybrid and bond market form a relatively narrow subset of the participants compared to many other asset classes, which could result in unusual trading patterns in the event of any unexpected development.

– Term deposits – risks in term deposits can be classified as ‘opportunity foregone’ as interest rates can change within the term structure or other investments present as better options.

Other asset classes – property, hedge funds, private equity, commodities:

Other assets have unique risks including liquidity, complexity and fees

Risks and opportunities:

– Liquidity is typically restricted in investments where the underlying asset cannot be readily realised. Investors should be paid a premium return over alternative liquid options;

– The capital value may be realized at a time when the valuation is not at its optimum;

– The holding structure can be complex;

– The fee base is often relatively high;

– The primary opportunity is to participate in assets which are difficult to access directly and a high degree of specialisation. Assessing the merits can be complicated due to limited information, comparable data and unique assets; and

Private investors may have noted the rising allocation to unlisted infrastructure and property by large superannuation funds as they look for income in a low yield world.

Conceptually, there is a good reason to consider these investments given stable income and security of fixed assets. For private individuals however, the merits have to be assessed independently of other investor groups. Pooled funds work on the basis of long term liability of their members, while anticipating that retiring members will be supplemented by new entrants, and are in effect acting in perpetuity. Liquidity is rarely required and they are able to directly manage the assets to reduce the costs and interest rate risk.

There are very limited options for an individual to participate and achieve an equivalent outcome. By nature, these assets are discrete and unique, lending themselves to individual consideration. Our view is that many of the investment structures on offer have high fees, clouded liquidity and redemption arrangements and do not necessarily represent the quality of assets that would suit most investors.

-

Risk

Primary concern is the loss of capital

From an investment perspective, the primary risk is the potential for capital loss.

While they are not one and the same, the investment community generally uses standard deviation as a measure of risk, both for individual assets and for investment portfolios as a whole. Investors demand higher expected returns for higher levels of volatility.

Standard deviation is the industry standard

Standard deviation, which is usually represented on an annualised basis, indicates how much an investment’s return differs from its average over time. The primary shortcoming of using standard deviation to measure the risk of investment returns is that it treats upward and downward volatility as equally negative for investors. Most investors would not be overly concerned if their assets only exhibited volatility on the upside!

A simple example that demonstrates this would be an asset that declines by 1% a month for a year (portfolio 1 in the chart below), compared to an asset that alternates between a 2% positive return and a 1% negative turn each month (portfolio 2). While the first asset has shown no volatility over the year, the investor would have lost 11% of their initial investment. The second asset would have shown some level of volatility, and a return of around 6% over the year.

Return Profile

Another issue in applying standard deviation to predict future investment volatility is that it assumes that volatility is symmetric on the upside and the downside, as well as assuming a normal distribution of returns. History has shown that this is often not the case.

Tail risks occur outside the predicted range

Tail risks are also generally underestimated by this analysis, that is, events that should be relatively infrequent in nature will occur more often than expected. These are typically associated with market crashes or financial crises, with modelling often failing to predict the extent of losses.

Nonetheless, standard deviation remains widely used for several reasons – it is relatively simple to understand, it is useful for modelling purposes, and it is simply the best tool that is available.

An investor’s time horizon is equally important when weighing up the level of volatility that they should be willing to undertake. Investments that are often volatile on a shorter-term time frame will generally exhibit a much narrower set of outcomes when measured on a longer-term basis.

By way of example, the chart below shows the rolling 10 year annualised return for the All Ordinaries Accumulation Index, from 1990 to 2016. While in a single 12 month period the returns range from -42% to 86%, over any ten year period the range is approximately 4% to 18% p.a.

All Ordinaries Accumulation – Rolling 10 Yr Return

Hence, the risk of capital loss for investments that appear to be volatile on a short term basis is often much smaller over the longer term.

-

Benchmarks

Major Equity Benchmarks, Fixed Interest Benchmarks

How to use benchmarks

The conventions of the institutional investment sector tie portfolio performance to a range of well recognized benchmark indices. In turn, the fund management industry uses designated benchmarks to provide an assessment of its capacity to ‘add value’. With the rise in exchange traded index funds, investors have even more reason to consider whether their portfolio can outperform these benchmarks.

In our view, non-institutional investors should pay heed to indices, but also acknowledge that they are not necessarily appropriate in measuring the desired portfolio outcomes. Unless the investor is willing to consider any index as the universe of options and not exclude any within its components (or include those outside of the index), the traditional indices will only be indicative rather than form the basis of performance measurement.

ASX200 Index and ASX200 Accumulation Index

The ASX200 is a comprehensive, familiar and appropriate guide to measure the capital appreciation of the Australian equity market, but it does ignore dividend distributions. The ASX200 Accumulation Index is more relevant and is the benchmark for the majority of fund managers. Frequently investor reports reflect only the capital position of stocks as a profit/loss and it is important to add in the income component when assessing the returns achieved over the holding period

Divergent trends within an index can be important

It is not uncommon for the index to disguise some broader trends. Until very recently, many small cap fund managers had outperformed the Small Ordinaries for several years by simply avoiding small resources stocks. The relative performance of a fund manager which does not invest in resources (typically even more volatile among small caps) must be viewed in this context, as the difference between the Small Ordinaries (and its industrials and resources subsets) can be stark as illustrated below.

ASX Small Ordinaries

Source: Iress, Escala Partners

MSCI All Country Index

The MSCI Indices are the common global benchmarks. However, there is a distinct difference between the MSCI World and the MSCI All Country. MSCI World comprises 23 developed country weighted indices whereas All Country includes a further 21 emerging markets. The MSCI Emerging Market index is also used for funds purely in these regions. If investors only hold developed country stocks, the World index is more relevant.

The performance difference over time has been stark as can be seen from the chart below:

Developed Versus Emerging Market Performance

Compositional mix influences returns

As global equity portfolios tended to be biased away from resource and financial companies, it is likely the ACWI would outperform the local index were those sectors to be out of favour. This is a key reason the Australian market outperformed global indexes in the mid 2000’s when both commodity prices and financial leverage were in play and contributed to the relative underperformance in the subsequent years.

This differential bias can be helpful in managing risk in the equity allocation

Hedged versus unhedged

An important decision is whether – and then how much of a global equity portfolio should be hedged against currency movements. Australian and global equity markets have a relatively high correlation whereas the currency adds an external variable which causes a greater divergence in performance.

As a rule of thumb, the smaller the global weight in a portfolio, the higher the unhedged component should be, as it then assists in diversifying risk. From a tactical perspective, the level of hedging can be varied depending on the assessed valuation of the AUD.

Bond market Indexes

The level of cash or bond holdings is a function of absolute returns and risk aversion. There are infrequent occasions when bonds can be excluded from a portfolio, such as with unusually low interest rates and at times of highly uncertain monetary policy. Otherwise it is the size and management of the bond portfolio which should be determined.

The measure of returns from the bond market is based on an index established by market participants as a convention. The bond index is a fixed rate government bond index, whereas the composite index also includes high grade fixed rate corporate credit.

Weighting is determined by issuance

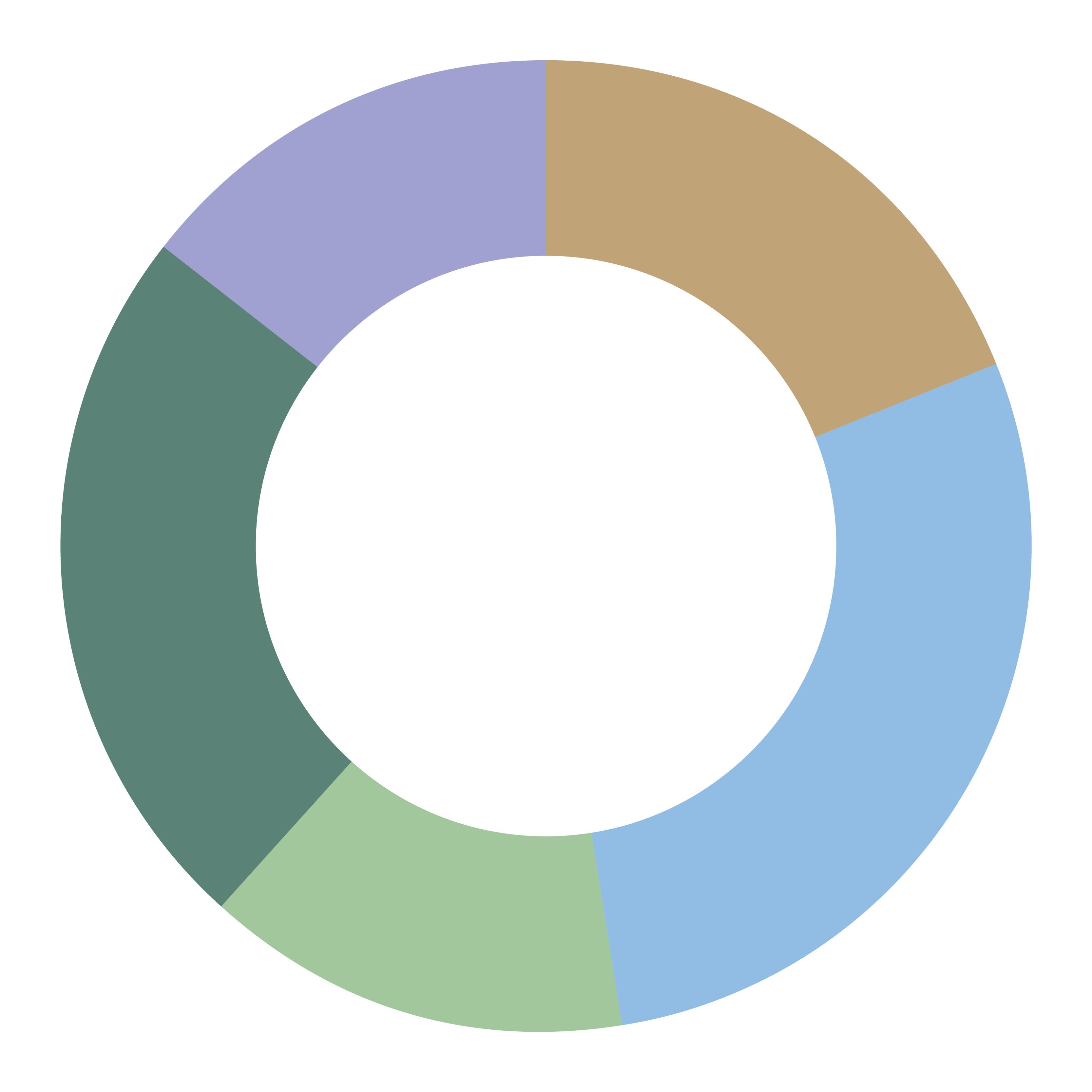

The Australian Composite Bond Index has seen a meaningful change in the weight of its constituents in recent years due to the increase in government bond issuance and the tendency for large corporations to issue debt into the US where interest rates have been much lower. The chart below shows the large proportion of the index which consists of government and quasi government bonds

Bloomberg Australian Bond Index, % weightings of constituents 2016

Source: Escala Partners, Bloomberg

Measuring the performance of a fixed interest portfolio against this well-known index may therefore be less relevant to private investors who are unlikely to hold such a large government and semi-government weight.

Listed Hybrids are not part of any measured index

Hybrids and listed bonds are not included in any published index. Therefore, a portfolio with these investments cannot be accurately assessed within the standard measures.

Global fixed income compositional change

The Barclays Global Aggregate Index has also seen substantial change as many government bonds have been downgraded. Conversly the weight of government (54%), semigovernment (13%) corporate (18%) and securitised debt (15%) has remained largley the same. As is the case with the other indexes, there are a range of securities which are excluded such as inflation linked bonds, some asset backed securties and any with equity like features.

Historical Composition of Barclays Global Aggregate by Credit Quality, Trailing 5 yrs

Source: Barclays Capital