-

Summary

Balance sheet and related metrics were out of the spotlight as central banks provided certainty on low interest rates. Rates are now rising, central bank balance sheets are tightening and, in many cases (including Australia), lending attitudes and structures are changing. In this edition, we have reviewed the economic framework and asset classes through the lens of a capital structure.

Central banks and the judgement of future conditions reflected in the bond market are increasingly influencing investor attitudes. Due to the rise in debt levels in the past ten years, financial markets are inherently more sensitive to rate movements than before.

Equities can produce positive returns in early stage of rising rates if economic growth is the cause of central bank adjustment. Equity styles do, however, change and it appears this is underway. Stocks that are priced on long term growth see a fall in valuation as future profit is discounted at a higher rate. Conversely, those sectors that can take advantage of economic conditions and a potential rise in inflation tend to do better.

Domestically, resource stocks are attractive given their cyclical position at a time balance sheets are, on aggregate, in good shape. Similarly, there are signs of a global shift towards sectors and regions such as energy, industrials and Japan. For high growth companies, there is some caution on the value attributed to their intangible value as regulation, privacy concerns and potential competition arise. We recommend balancing equity allocations between longer-dated conservative growth strategies and those that are biased towards the value segments of the market.

Increased attention to balance sheets for credit exposure is a repercussion of higher rates and the growth in corporate debt. Allocations to the asset class can be clearly designated between that for defensive purposes, such as modest yielding corporate credit or uncorrelated sovereign debt. High return-seeking investors have turned to other instruments, including asset backed and alternative debt structures. These require increased oversight due to the greater risk of default and higher portfolio concentration.

We have held to our neutral tactical (compared to strategic) allocation to equities. While rate markets are more attractive, it is too early, in our view, to take on duration. Higher balances in term deposits will limit volatility that may come from dislocated markets as we enter a change in pattern.

-

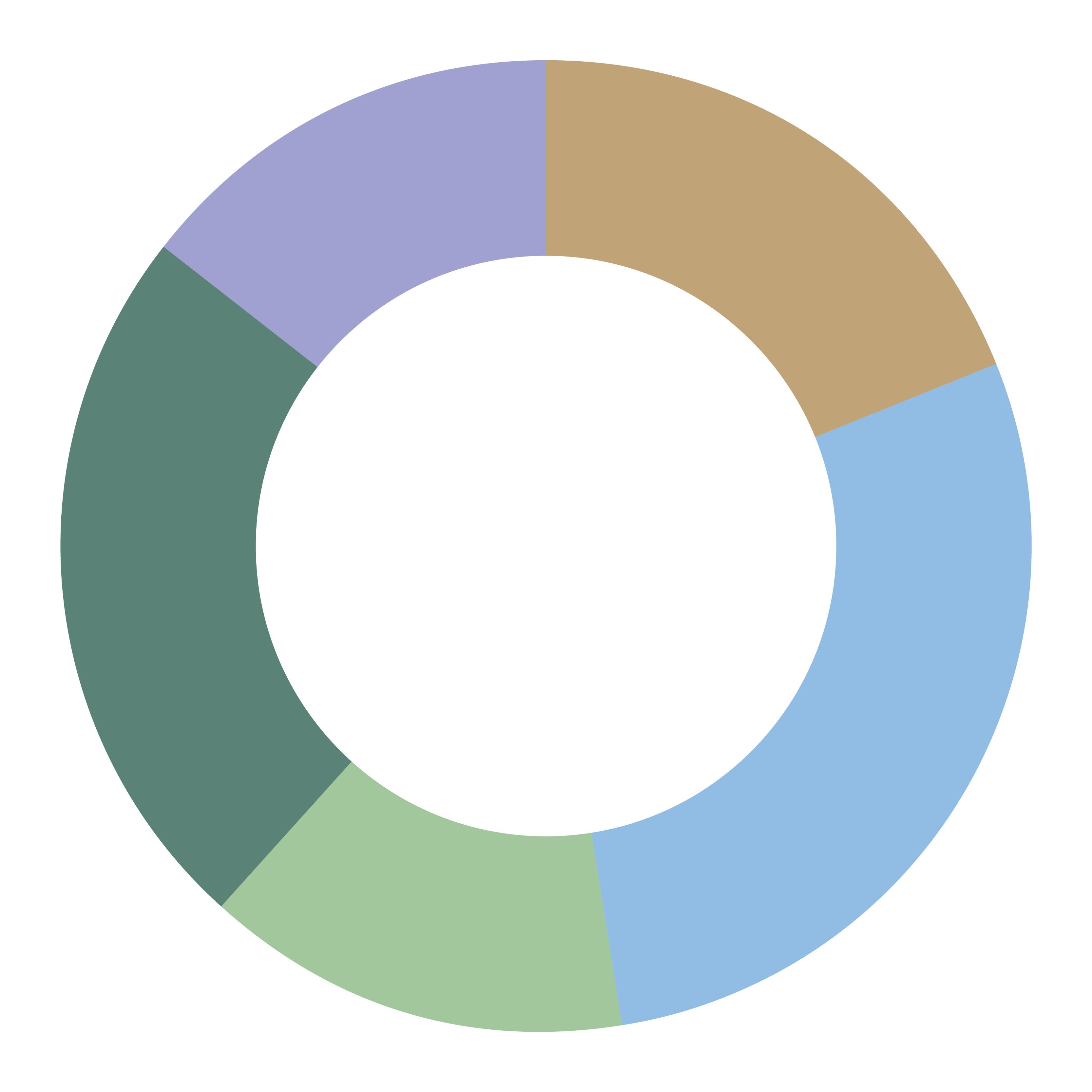

Asset Allocation

-

Expected index return (excluding alpha and franking)

-

Expected index return (including alpha and franking)

-

Expected returns

The tailwind for asset classes from low rates is at an end. While the earnings outlook for equities is relatively attractive, the valuation is showing signs of reverting to the mean. Stock price changes are proving reactive to small changes in profit expectations and equity performance is expected to become sporadic.

Fixed income is beholden to the coupon, spreads and rates. Capital gains are less likely and will reduce the overall return from the asset class.

We recommend a reassessment of an investor’s risk profile. Aiming for high returns is likely to come with higher volatility than recent times, not only at an asset level but within individual strategies.

-

Investment Outlook

There are two changes afoot that will impact financial conditions:

1. the price of debt is rising, even where official rates are anchored and,

2. there is a major shift in the quantity and source of liquidity across the financial world.

The combination of falling cost of debt and availability of liquidity has had an undeniable and probably determining impact on investment markets. Fixed interest assets provided high returns of 6-8% p.a. for 10 years (at an index level), combining low coupons with capital gains. Equity participated in asset price inflation across the board, and particularly so for growth equities that are valued at long term discount rates. There is little question that investors were pushed into assets and risk levels that would not have been the case had there been adequate returns on traditional risk-free assets such as government bonds and term deposits.

The other cited truism is that investment cycles don’t expire with a designate time frame, nor does a recession bring about a fall in investment values; rather the other way around. What invariably has resulted in pullbacks (and the degree varies considerably) is a combination of excess valuation, leverage and optimism.

Before we become overly cautious, there are investment assets that are not excessively priced. Indeed, the bifurcation of valuations in equities is readily transparent, while it is likely that subsegments in fixed income will also become less correlated as rates diverge.

-

Economic Outlook

Amongst the many comments on the ten-year anniversary of the onset of the financial crisis, is an indisputable fact: aggregate global debt levels have continued to rise. The mix, however, is now quite different. Developed economy governments have been the main contributors, while that for corporations and households is nuanced to each country. Post the downturn, advanced economies fiscal support and low GDP growth has taken the sovereign debt/GDP from 69% in 2007 to 105% in 2017. While emerging economies have been contained, with government debt/GDP at 46%, there are well known problems in several countries. Interest rate sensitivity is therefore inevitably higher and policy decisions will have a larger impact than before.

There is a widely held view that high debt levels inhibit longer term economic growth. The case is arguably somewhat more nuanced; low debt levels provide optionality in the event of a downturn, as well as reducing the volatility in growth, as one would expect from operating leverage. Recently, a paper from the IMF noted that the level of debt in any country depended on its serviceability. Important to this are the interest rates relative to the nominal growth in GDP, the maturity of the debt, whether the holders are local or foreign and any constraint; for example, exchange rate flexibility.

A debt-funded cycle from an already elevated level can engender growth, if the potential return is viewed positively. A current example is the US, where deficit funding is supporting a large fiscal stimulus.

The US carries risk that Treasury yields may rise more than expected, as few are predicting the 10-year bond yield to reach above 4%; roughly the cycle midpoint of nominal GDP. If the recent comments from the Fed Chair hold water, the cash rate may go above its so-called neutral level given the rise in economic activity and imply a 10-year bond yield of closer to 5%. The mix of holders of Treasuries may prove the key issue. Global surpluses have been skewed to USD holdings given its status as a reserve currency. Surpluses are dissipating (for example China’s current account is neutral to negative), Japan is likely to realise some of its foreign holdings as the aging demographic is funded, while oil-rich countries, notably Saudi Arabia, are now running fiscal deficits that require their own funding sources. If the buyers for US Treasuries do dry up, more debt will be held internally and displace investment flows to other asset classes.

In Europe, the call for an end to accommodative monetary policy is rising. Its purpose is no longer clear, arguably more about supporting the Euro project than sensible policy. The argument for a rise in rates has one foundation. European banks are sitting on $2000bn in cash deposits with a negative return. Even a modest positive outcome would realise a return on this capital, improving their balance sheets and capacity to lend. Meanwhile, Europe is also coming under pressure to relieve the fiscal constraints imposed post-2008, in part due to populist political sentiment.

The corporate sector has taken full advantage of low interest rates while moving to bank funding from credit markets. Chinese companies and state-owned enterprises have been the most notable, though the US corporate sector has also structured its debts to credit on availability and price.

Global non-financial corporate bonds outstanding ($tr)

Source: Dealogic, McKinsey Global Institute analysis

The Bank of International Settlements has noted that the retreat of banks from highly leveraged lending has left capital markets and asset management exposed to credit risk. The private sector has stepped into higher risk/higher return products as banks rebuilt their balance sheets or were constrained by regulation.

Akin to the outcome when the banking sector found itself too lightly capitalised to cope with counterparty risk, the asset management sector may see sharp withdrawals from funds if there is a view that the creditors could default. Once again, there will be a broader effect from a reduction in funding for consumers, small businesses and the property sector.

Further vulnerabilities lie with a mismatch of cash flow, the most notable being Emerging economies hard currency (US, Euro) debt where there is no revenue or profit in those currencies. This would apply to their domestic sectors such as property or bank funding. It could also be the case for the broader corporate sector, which has longer maturities that may require refinancing at a difficult time.

Central banks tend to be better at strengthening financial systems than preventing excess credit growth in the first place. In almost every region, the cost of funding is rising and should, in time, reduce the rate of increase in debt. The challenge will be to understand the tipping point before the contraction has a negative compounding effect.

Already it is increasingly obvious that regional disparity is rising. A lower availability of capital at a higher cost will reintroduce selective investment.

-

Australian Equities

While the Australian economy escaped the worst of the economic crisis (technically avoiding a recession), what may be surprising to some that the Australian equity market lagged many other developed markets through this recovery phase.

The structure of the Australian equity market has no doubt played a part in this outcome. A high weighting in the resources sector (while commodity prices have staged a recovery in the last 2-3 years, the majority are still well below their pre-2008 peak), large sectors such as the supermarkets and telcos have faced structural and competition headwinds in this time, and regulatory and/or political intervention has been problematic for a range of industries.

A factor which has received less attention, was the relatively high level of equity issuance through the financial crisis (particularly by companies that were unable to refinance maturing debt) which diluted the returns. In 2009 alone, equity issuance represented 9% of total market capitalisation, much higher than other markets, such as the US (~2%) and the UK (~6%).

The state of balance sheets clearly matters for individual company equity returns given that those facing balance sheet pressure are often sold down based on equity raising risk. This can be ignored during extended periods of profit expansion and/or a falling interest rate environment.

The chart illustrates the one-off impairments of assets, goodwill and intangibles over the last decade. While writedown risk should be assessed on an individual company basis, at an aggregate level it is quite a poor reflection on the investment decisions made by ASX companies over a long period. In total approximately $186bn has been written down over this time, or around 10% of the total market capitalisation.

ASX 200: One-off Impairments of Assets, Goodwill and Intangibles ($bn)

Source: Bloomberg, Escala Partners

Given the extended earnings recovery experienced since 2009 (only interrupted by a collapse in resources profits five years ago) and the risks that Australian bond yields will trend higher in coming years, we discuss how the various sectors of the Australian market are placed in context of their capital position.

Banks

The balance sheets of the major Australian banks are in good shape. While this has been assisted by a very benign bad debt cycle, the primary driver of the strengthening of banks’ balance sheets in recent years has been regulatory in nature. The catalyst was the 2014 Financial System Inquiry (FSI), which recommended that APRA set capital ratios of authorised deposit-taking institutions as “unquestionably strong”. The definition of “unquestionably strong” was last year established as a 10.5% common equity tier 1 ratio, with the four major banks given a timeline of January 2020 to meet this new target. Each of the major banks has now broadly meet the minimum ratio via equity raising and dividend reinvestment, although notably have little buffer above this benchmark. ANZ is best placed among the majors, while NAB is in the weakest position.

From a profitability perspective, the return on equity (ROE) across the sector has reduced due to the contraction in balance sheet leverage. In the absence of any future relaxation of capital requirements, the decline in ROE is thus structural in nature and is an important consideration in the valuation.

Regulation remains key. From the perspective of the banks, the primary outcome from the Royal Commission is expected to be tighter lending standards (i.e. higher enforcement of available credit to households with limited disposable income) and hence limited credit growth. Investors are primarily holding the banks for their high dividends, and while there are varying degrees of dividend sustainability among the majors (and due to capital buffer, ANZ is judged sustainable while NAB’s dividend is less secure), these are assessed as broadly safe in the medium term if there is no normalisation in the bad debt cycle.

Resources

Within the major sectors, the resource sector has amongst the strongest balance sheet from an aggregate perspective. The current situation has been borne out of a period of very high commodity prices, rapid payback on new projects and therefore excess investment through the early part of this decade. Commodities subsequently collapsed, unable to cope with a wave of new supply and slowing demand. Following this was a series of asset and goodwill impairments, capital raisings and balance sheet repair. Resources are disproportionately recognised in the chart above, occupying 14 of the 15 largest asset writedowns, the 3 largest goodwill and the top three in intangible writedowns.

Balance sheets have since recovered, helped by capital raisings, a large scale back in capex and repayment of debt. The decision to reduce capex has been well supported by shareholders given the prior period of poor investment and the general preference for income, and has translated into very high free cash flow yields and increasing dividends. Profit margins, too, are trending back towards cyclical highs, although may be constrained by rising inflationary pressures. Metrics such as ROE and ROIC are less useful now as they are inflated by the aforementioned writedowns.

The outlook remains quite sound, with valuations reasonable, earnings holding up and further possible capital returns. Volatility has increased in recent months given the uncertainty created by US trade policy. While base metals have peeled back, possibly driven more by sentiment, bulks (iron ore and coal) and oil have remained high, with these latter three more important for the profitability of the aggregate sector’s earnings. The lesson from the sector is that periods of low capex can be shareholder friendly compared to aggressive pursuit of growth.

Industrials

Across the various sub sectors of the domestic industrials market, there are differing degrees of leverage and sensitivity to higher bond yields. On aggregate, however, industrials are judged to have a low level of gearing and relatively high interest cover.

Industrials have generally been ahead of the other large sectors in strengthening balance sheets over the last several years. The immediate focus for shareholders, however, has typically been for higher dividend payments (companies that have delivered on this front have enjoyed a P/E re-rate), which has lifted the dividend payout ratio.

‘Bond proxies’ are a highly leveraged group of companies and thus are most at risk from changing conditions. Australian domestic rates have remained subdued and thus the impact on infrastructure, REITs and utilities has been relatively immaterial, yet the performance looks to be capped in the medium term. A recent development has been an extension of their debt maturities, slowing the impact of any future rise in yields.

From a valuation perspective, it has been the high margin, asset-light sectors that have experienced the strongest returns in recent years, particularly in the information technology and health care industries. Price to book (P/B) ratios are naturally higher for these companies, particularly those with high levels of intangible assets such as brands or intellectual property created via research and development investment. Nonetheless, P/B ratios have continued to expand, most notably in healthcare, which has gone from a P/B ratio of 3X in 2012 to almost 7X today. Within this cohort, companies the majority are self-funding, rarely accessing capital markets, and growing organically, arguably deserving of a premium given the stage in the cycle.

Style has been a large determinant of Australian equity portfolio performance through this year, with a relatively narrow set of high earnings growth companies re-rating, along with the cyclical uplift from the resources sector. While there have been some early signs that this phase may have run its course, improving domestic economic conditions and rising interest rates are the more likely catalysts for a rotation into ‘value’ equities.

The balance sheet of Australian listed companies appears sound at face value. However, high dividend payout ratios leave little leeway if the earnings outlook changes. Further, acquisitions invariably require equity raisings. Currently, the resource sector is viewed as best positioned, with shareholder-friendly capital management and possible under-estimation in the extent of the commodity price cycle.

-

Global Equities

In a sign of the times, General Electric (GE) was removed from the idiosyncratic Dow Jones Index, followed by a $23bn write off in goodwill from its balance sheet this month. The problem arose from GE’s acquisition of the energy business from Alstom in 2015 where the level of debt and existing cost liabilities outweighed the book value of assets. The much-heralded synergy and cross-selling benefits did not eventuate, and new management have effectively now distanced themselves from the past.

While GE has been struggling for some time, it was a salutary reminder that the structure of balance sheets is often a neglected part of financial analysis. In the US, 54% of companies have more goodwill than equity, exhibiting a steady rise over the past decade.

Goodwill as a proportion of equity (median on median)

Source: Bloomberg, Deutsche Bank

Another way of presenting the data is at a national level, where investment spending is increasingly dominated by computers and intellectual property, as opposed to structures and other assets. The implications are widespread, changing the time frame of the asset base and a likely reduction in capital flexibility as fewer fixed assets can be realised.

Non-residential Business Investment as a share of GDP

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, Citibank

The accounting of assets in a balance sheet varies across regions, such as the revaluation of property assets, or the treatment of non-performing loans in banks. Company management may, to an extent, decide on how to express their view in the accounts; for example, when raising provisions. Then there are changes to standards, such as the recent requirement to bring off balance sheet leases into the stated accounts. These issues require a proper assessment of financial assets and liabilities that can change an investment thesis. With the market inevitably focused on short term earnings, it may mean a portfolio can deviate from an index by exercising caution on the potential problems that may only arise in the long term.

Goodwill should reflect future cash flows of a company, a challenging forecast at the best of times. The super charged growth of high profile technology-based services companies has belied the risk that these companies’ business models rely on intangible assets that are inherently hard to value. Fixed assets can be reasonably judged by their replacement costs, the rate of depreciation as an indication of useful life and the annual maintenance capex undertaken. Sustaining brand value that is dependent on successful marketing, R&D and product or service upgrades is harder to assess.

Several considerations arise for equity portfolios:

– Metrics outside of standard P&L data require an appropriate understanding of the balance sheet. For example, screening on price/book may be misleading if the book value does not reflect revalued assets, while intellectual property and brand value is often unrepresented.

– Buybacks and dividends, when they exceed net income, create a distortion in the equity base and therefore ratios such as ROE and changes in ROE.

– The distinction between some operating expenses (incurred through a P&L and intended to reflect ongoing costs) and capitalised assets on the balance sheet is increasingly blurred.

– Assessing R&D (which is expensed) is key in some equity sectors, particularly healthcare, and can create a multi-year payoff that is valued on a long-term discount rate, itself a debating point.

– Management can forgo capital intensive growth opportunities or limit capital spending to show higher short-term returns. There are many examples of high-profile companies that lost their value as they failed to generate new strategic assets. Others may undertake risky short-term investments to bolster the appearance of growth.

It is common to adjust reported accounts gain a better sense of the true value of a balance sheet. A purist may add back all write-downs, depreciation and other non-cash charges to get a true sense of free cash flow and capital invested. The flaw in this approach is that the current investor does not pay for past mistakes and often there is new management that is taking a different approach.

Earnings expectations are generally based on company guidance and therefore changes to the outlook result in a sharp share price reaction after the event. A focus on factors outside of predicted earnings and P/E is likely to become more important as equity leadership shifts from its concentration on a select number of high growth companies.

The dominance of intangible assets and several well-funded private equity held companies suggests that not all will win and that the profit margin of some favoured stocks could come under pressure.

The emphasis on balance sheet valuations varies in regions and sectors. The US has historically been skewed to earnings metrics, while for Asia and Japan price to book is usually cited as the key metric.

The chart shows the sector price to earnings and price to book spreads relative to their history. What stands out is the very high P/B for IT, Consumer Discretionary (which includes Amazon) and Industrial stocks, while for all other sectors this measure remains subdued. In our view, there may well be a rise in book value for IT and related companies as they invest in automation (for example, Amazon) or increase their local content (for example, Apple). Conversely, the potential for a large rate of change in earnings in sectors such as energy and financials is high, while P/B is well below historical levels.

Percentile of current relative valuations of developed market sectors

Source: MSCI

The US market has traditionally been predominantly driven by short term earnings, with most attention on the quarterly reporting periods. This year, the combination of tax changes, repatriation of cash to repay debt or undertake share buybacks and the ability to write off capex has distorted balance sheet ratios. Nonetheless, there is a growing opinion that the relative valuation between sectors is the most stretched.

We note that most funds are at or below index weight to the US and have moderated their positions in high profile growth companies. A tilt towards a value orientation aligns with a view to capturing some of the balance sheet factors noted above.

Opinion on other regions is divided. The most favoured region is Japan, where the trend in corporate governance is progressively resulting in higher earnings along with stable balance sheets.

Profits and return on equity

Source: JPMorgan

All data sets show that the Emerging Market Index is the most undervalued compared to history and other regions. This applies to both P/E and P/B. An example is Korea, trading on 7.7X forward P/E, a P/B of 0.9X and a respectable ROE of 12%. Earnings growth is forecast at 6% for 2018/9. By contrast, the Asia/Pac ex Japan index is trading at a P/E of 11X, P/B of 1.4X, yet has similar earnings growth and ROE. In both cases there are stock-specific and other factors at play, but it is indicative of the potential for patient investors to participate in a re-rating.

We rely on the fund managers to consider relative value in regional stock selections. While there is uncertainty in the near term, the earnings outlook in non-US regions, a price to book screen and longer-term ROE trend should provide support.

Real estate investment trusts

REITs need to consistently raise capital to grow which can be sourced from undistributed cash flow, equity raisings or debt. Debt is usually the most common, especially in this low interest rate environment. New properties need to be funded by a cost of capital lower than the cash yield for dividend growth to be supported. As rates rise, growth may therefore slow and capitalised values retreat, a double headwind to the sector. Additionally, the income produced by REITs becomes less attractive compared to that of fixed-income products that provide lower risk.

However, rising interest rates are associated with economic growth and increasing inflation, which can have a positive impact on REITs. Vacancies usually dissipate into a business cycle which can allow for higher rents. At the same time, inflation is sometimes built into rental rates.

The degree to which rising interest rates impact property investments can be determined by the degree of leverage defined by Debt to EBITDA or debt to total assets. The FTSE EPRA NAREIT Developed Index, which tracks the performance of listed real estate companies and REITS worldwide, illustrates that REITs have constrained their appetite for debt, notwithstanding low rates.

FTSE EPRA NAREIT Developed Index debt ratios

Source: Bloomberg, Escala Partners

Similarly, REIT’s interest expense as a share of net operating income has decreased over the past ten years. Furthermore, they have generally taken advantage of low rates by extending the length of their debt to nearly 6 years.

US Listed REIT Industry

Source: NAREIT, Escala Partners

The assumption that the performance of REITs is correlated with interest rates is due to the connection between cap rates and interest rates. Cap rates have moved to historical lows and the resulting capital gain is unlikely to be repeated. To date, there has not been much movement, though it typically takes a few years before rates feed their way into revaluations.

REIT Implied Cap Rates and BBB Corporate Bond Yields

Source: Citibank, Bloomberg

In aggregate, the combination of lower leverage and interest expenses reduces the risk to REIT returns. In our view the fundamental demand within sectors and regions will now be the primary driver of performance rather than rates and valuations.

-

Fixed Income

The investment proposition for fixed income differs to equity. The optimal outcome when purchasing a bond is that it will pay interest and repay the loan at an agreed maturity. To assess the likelihood, the focus is on the company’s balance sheet of outstanding debt, funding costs and the income available to meet interest payments and payback capital. Profitable growth is only relevant in its purpose to support the distribution and capital return.

Investment grade credit

For defensive positioning within fixed income, investment grade (IG) bonds provide a higher yield than sovereign bonds, while still offering capital preservation. Default rates in IG credit are extremely low, and reduced volatility and strong corporate profits in recent years have made for a safe investment. Credit spreads are tight and have remained so even as supply has risen.

Low interest rates and improved accessibility have encouraged corporates to borrow more, including lower rated companies. The IG bond market has grown from US$4.8 trillion in 2008 to US$9.3 trillion by June 2018. With this, so too has the weighting of BBB rated issuers as a proportion of the investment grade bond sector, rising from 25% of the IG market to almost 50% today. This increased supply has been met with demand from non-bank lenders, hedge funds and pension funds and, in some cases, in competition with central banks.

The growth of BBB rates bonds as % of investment grade bond market

Source: Bloomberg, Barclays

For investors in IG credit, the repercussions are that the universe is made up of a higher weighting of lower rated companies (BBB issuers) and higher debt ratios. Most sectors in IG are near ten year highs in terms of leverage. While this composition change has been unfolding for years with no rise in default levels or even price volatility, it will become relevant as global interest rates rise and if growth stutters.

Debt to last twelve months’ EBITDA

Source: JP Morgan Asset Management

Credit selection and capital structure positioning remains key as Debt to EBITDA varies across sectors. A notable example is banks where many have reduced debt, cleaned up balance sheets, increased capital ratios (US and European banks tier 1 capital ratios have risen from an average below 4% in 2007 to more than 15% today) and become generally safer, albeit less profitable.

Domestic hybrids

Domestic bank hybrids continue to provide income, although this may be reduced if Labor is elected and changes the accrual of franking credits. Our preference, therefore, is for hybrids that mature in the next two years. Limited supply in the second half of 2018 and an upgrade in the domestic major banks stand-alone credit ratings (which is under review and could lift hybrids from BB+ to an IG rating of BBB-) would be a positive outcome. Elevated BBSW and Libor rates and limited interest rate risk have translated into more attractive term deposits, bank hybrids and floating rate corporate bonds.

We remain comfortable with global and domestic floating rate IG credit bonds but note headwinds on credit spreads should US interest rates rise excessively, concurring with bond refinancing which is at record levels in the next five years. We recommend a mix of IG credit, TDs and short dated domestic bank hybrids.

High yield

Similarly, the high yield (HY) market is likely to perform in the short term as fundamentals remain strong, interest cover ratios are trending up, and default rates remain low at 1-1.5%. While leverage is declining, it is still high, averaging 4.5 X EBITDA within the sector. As interest rates rise, and debt comes up for renewal, high yield may prove vulnerable. Low issuance levels in this sub sector in 2018 have aided valuations, but a change to supply may be the catalyst for price weakness.

Our recommendation is to have a diluted exposure to this sector, investing in managers which have a preference for shorter maturities in selected names. We are neutral over a short timeframe, but are cautious over a longer time horizon as high leverage and refinancing requirement increases the risk of defaults.

Sovereign bonds

For developed economies, the increased leverage in the last ten years is often a second consideration and not the main driver of valuations. Our long-held view is for higher global yields led by the US Fed rates and central bank balance sheet reduction, fiscal spending policies and tax cuts that will be funded through increased treasury issuance. Rising oil prices, tariffs on imports and potentially wages could spur inflation, while a temporary easing in demand from pension funds post the tax change incentive date may weigh on prices. That said, we expect yields to be capped as investor demand at the higher rates from those underweight to treasuries (albeit hedged positions are still posting a negative return for many offshore buyers). In Europe, monetary easing is ending and rate rises are being priced for late 2019. Australian rates are on hold, with a similar upward trajectory of rate rises priced in from October next year.

Our recommendation is still underweight developed market (DM) sovereign bonds, although the recent higher yields suggests that the time for adding duration is getting closer. On US treasuries, opportunities are likely to arise in the near term to add ‘insurance’ as a mitigator to a downturn in risk assets. Lengthening duration in Australian and European government bonds would be premature and we remain underweight in these regions.

Higher US rates, trade tensions, a Chinese slowdown and strong USD plus additional country-specific problems have impacted negatively on emerging economies. Countries with significant amounts of offshore short-term debt, large current account deficits and high inflation have been the worst affected, although most countries in the region have indiscriminately been sold off as funds flow out of EM in favour of DM.

Year to date emering market returns vs current account

Source: Citbank

Analysing a specific country’s fundamentals and balance sheet is key to obtaining long-term performance in EM, while acknowledging the volatility in the returns. We recommend the Legg Mason Brandywine GOFI Fund for this exposure.

Securitised bonds

The outlook for US securitised products remains sound (outside of auto and student loans). Residential Mortgage Backed Securities (RMBS) have improved since the financial crisis with better structures and tighter lending standards, lower loan to values (LVRs), low delinquency (missed mortgage payments) and greater subordination.

The Australian market is more vulnerable given high debt to income ratios and housing costs. Further, any changes to negative gearing, out of cycle rate rises by the banks and restrictions on lending may accelerate a fall in house prices. Nevertheless, structures with decent subordination and excess spread, combined with the recourse nature of our mortgages, low unemployment and a current 1.2% arrears rate on public RMBS deals should ensure capital protection, but short-term price weakness on some tranches may result.

We continue to support funds that have holdings in RMBS based on their approach to each selected tranche.

-

Alternatives

Alternative debt

Global investment into private loans has increased, with Australia late to this trend. Loans are usually to companies below investment grade and secured against a pool of hard assets (buildings, equipment etc) or contracts and cashflow of the business. While still in its infancy, the benefits of the domestic market versus offshore is typically higher credit quality, shorter tenor (average five years) and tailored terms and covenants. On the other hand, locally the borrowers are concentrated in industry sectors or household cohorts.

The covenants allow the lender to enforce a repayment of debt if the company is in breach of leverage levels, interest coverage ratios and debt service coverage. While it may not prevent a default, it will give the lender early warning signs and potential control to work towards a resolution. As these loans are illiquid and unrated, and market data pertaining to defaults and recovery rates is unreliable, performance is heavily dependent on the fund managers ability to assess the balance sheet and credit quality of the business.

Recommendations in this sector are investor specific. We review the product suite based on a wide range of criteria inherent in the broader outlook (for example in property or personal loan growth, the details of the fund itsel, such as the structure of the product and diversity of the loan pool).

Australian Strategies

Alternatives equity funds remain a useful diversifier of risk in investor portfolios, particularly given relatively strong equity returns over the last few years and rising P/E ratios. Similar to assessing individual equities, funds also use varying degrees of leverage, which will have the effect of amplifying the returns of the portfolio and creating a higher level of volatility.

Within our recommended funds, Bennelong Long Short utilises the most leverage, with an average of 4.3x net asset value since inception and 4.6x as at the end of September 2018. Comparatively, ARCO Absolute Return and Ellerston Market Neutral both have the capacity to use leverage, although have historically used little to no debt in their funds.

A blend of market neutral funds can be constructed to an investor’s individual risk/return profile with leverage a key determinant of the volatility of the strategy.