-

Introduction

In this quarterly we discuss the degree of concentration that can be an unintended consequence of portfolio selections. We aim to express a particular set of circumstances in our recommendations, while acknowledging that there is no certainty in that conclusion, or that investors have the appetite to change direction frequently. The portfolio therefore has some diversity and safety valves in the event circumstances are different.

We take a view over about a 12 month time frame, but our investment returns are formed on the expectations across a three year period, which allows for some inevitable influences that cause short term momentum.

Our recommendations are unchanged from earlier this year. In the first quarter growth and risk asset classes went through a sharp downward cycle, yet have largely recovered that ground. Nonetheless, we do not have sufficient conviction in growth assets to increase our weight. The extent of possible returns does not compensate for the risk of another pullback.

The expected total returns over a three year view are between 5-6% p.a. Low economic growth and low interest rates inevitably mean investment returns are likely to be below historical outcomes, while still achieving a return well above inflation. The figures below make no allowance for franking benefit or potential returns, or ‘alpha’ above the benchmarks.

-

Diversification versus Concentration

Finding the most appropriate balance between diversification versus the risks of concentration is a familiar topic amongst the investment community. While an asset allocation approach is the bedrock of portfolio construction, it can cloud the risk factors across the portfolio. The predominant measure of risk in investment assets remains the volatility of returns. In this quarterly report, we address some of the other influences, in particular, the correlation within assets that may result in unintended risks.

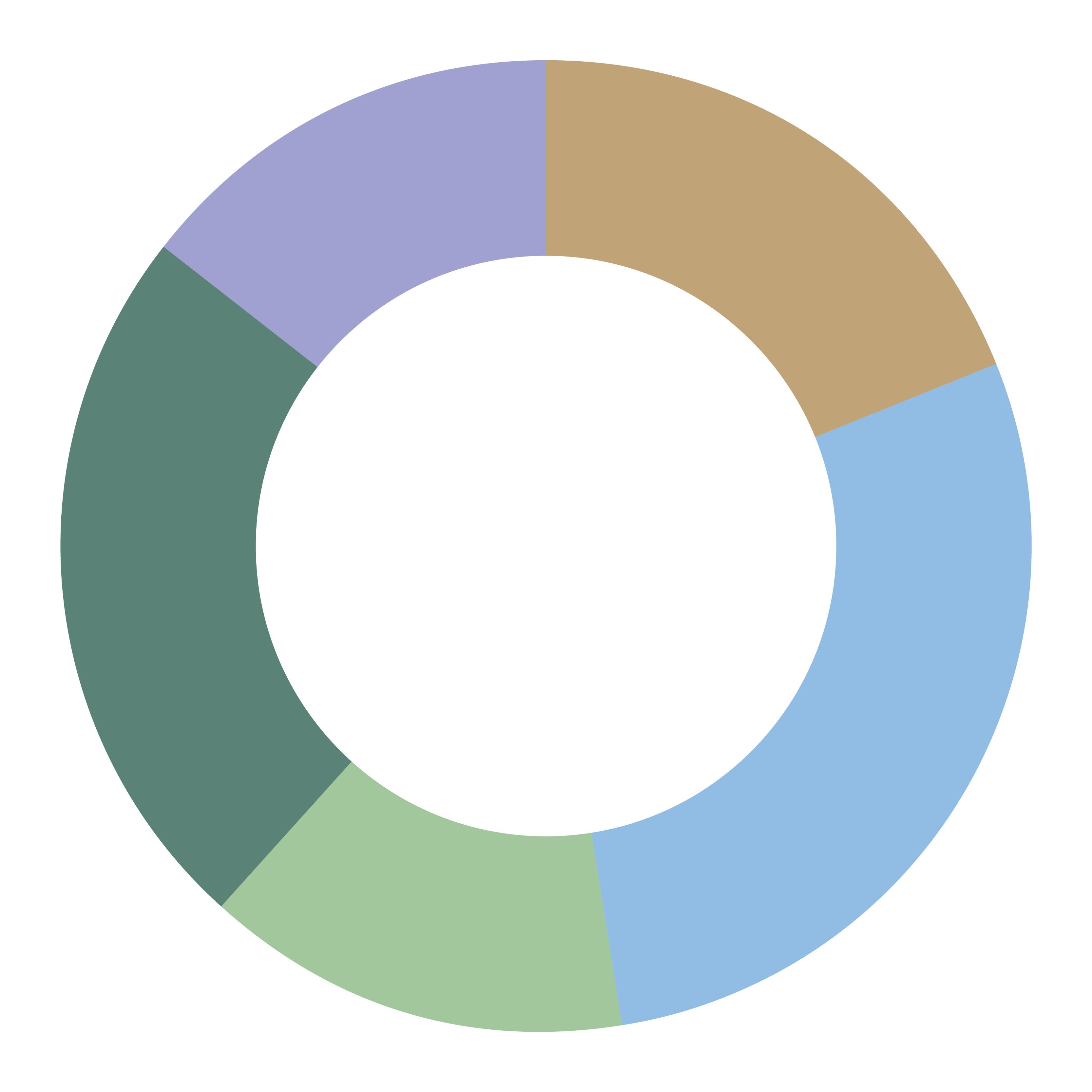

Each asset class has a set of factors which underpin the returns. A typical illustration is shown below.

Macro Building Blocks for Asset Classes

It is natural to focus on the economic direction as the commentary is frequent and relatively comprehensible. Few, however, talk about interest rate premiums or inflation risks to the same extent. The intention of asset allocation is to ensure there is direction to the portfolio, in that it takes a view on the value in each of the components shown above, while also being measured on concentrating the risk behind any factor. An example is the credit premium in corporate bonds, the premium in emerging world assets and the economic premium in equities which tend to be highly correlated, particularly in the short term.

In practical terms, this was most evident in the first quarter of the year. With the sharp fall in energy prices, corporate spreads widened, pricing in higher default risk in the high yield sector. In turn, emerging assets came under pressure, as a number of developing countries are reliant on commodity markets. The fall in oil prices was in part due to oversupply, but moderating global growth was another unhelpful component and equities across the globe took a hit. Risk in energy defaults highlighted the exposure of the banking sector to commodity companies and, while it is relatively low, came at a time bank capital structures were under scrutiny.

The purpose of this example is that there can be a high concentration towards one event which has counterparty risks. Just eliminating all holdings in energy, both through the commodity or the stocks, would not have saved the day as the impact was far wider. It is clearly near impossible to isolate a portfolio from such outcomes, yet it is worth considering the possible linkages and how they can be mitigated.

At an asset level there are a number of tools and concepts that are used to limit these risks. The most common is the correlation of indexes.

The table below shows the 15 and 3 year correlations. It is worth emphasising that this data shows the direction of movement between asset classes and not the magnitude; a high correlation therefore says little about the level of returns.

Asset Class Correlations

Source: Bloomberg, Escala Partners

Source: Bloomberg, Escala Partners

Of note is that correlations are far from fixed, varying over time and due to a range of circumstances. Broadly speaking, however, it is clear that equities have a relatively low correlation to fixed income assets, which underpins the long held tradition of a 60/40 portfolio as ‘balanced’.

The currency adds a dimension of its own. Unhedged global equities show the impact and this speaks to adding unhedged equities in achieving lower volatility in portfolios.

Recently, cash has been unusually correlated to equities. On a one year view (a dangerous time frame given the small number of observations) cash (bank bill swap rate) has a much higher correlation to equities (0.47) than fixed income (0.11). This can be explained through interest rate expectations. A small fall in the cash rate would in the short term imply economic conditions are deteriorating, inducing equities to decline.

In summary, we observe correlations and endeavour to understand if there are any specific factors which may be influencing the asset classes. The most common are interest rates, inflation expectations, currency volatility and the structure of the underlying index. This last mentioned feature refers to the different weight of government bonds to corporate credit in local versus global fixed income indexes and the high bias of the Australian equity market to financials and resources relative to the MSCI index.

Examples of the way we express our views given current economic trends are:

Low Economic Growth versus Recession

A low growth environment underpins our guidance of low investment returns with a bias towards the corporate sector through equities, alternatives and credit. Government bonds and cash are the two most reliable assets in severe downturns. We recommend some exposure, as detailed later in this report, depending on the desired outcome of the portfolio.

Inflation versus deflation

A modest rise in inflation looks likely in the US (wages, healthcare, rent), while in most other regions there is no evidence of any upward trend in prices. Low inflation can hamper the equity sector as it indicates companies have little pricing power. Low wage growth, while helpful for profit, subdues consumer demand over time. This suggests credit returns will be best together with a selection of equities that are able to extract profit from market share gains or changing industry structures.

Deflation is harder. Nominal debt repayments become problematic and implicitly credit may be less safe. Equities are unlikely to have much appeal. Longer dated government bonds (assuming some yield) and cash would act as a buffer.

Rate rise versus rate cut

For the US, the tail risk would be no rate rise, rather than a rate cut. Conversely, in Australia the question is whether there will be another rate cut rather than the risk of a rise. The lack of conviction in the US on the rate cycle is acting as a sentiment dampener as it suggests the Fed is concerned about the economy, or alternatively will find itself behind the curve if inflation emerges. In our view, a rate rise in June would be helpful to investment markets, particularly equities, though the US may lag as tighter funding conditions are factored into the market. A no rate rise scenario puts the investment case firmly behind credit.

Domestically, a rate cut can be expected to put a floor on income producing assets even though it would indicate economic weakness. Both credit and equity markets are likely to return in line with their distribution yields, with potential capital gain from duration.

Tail Events

China growth acceleration versus a dramatic slowdown

We see either as relatively unlikely given the centralised system. High growth would accentuate longer term issues through credit expansion and likely property risks; a sharp slowdown may result in political instability. The tail risk may be an extreme reaction by the governing authorities such as capital restrictions and trade barriers. However, this would unwind much of the progress that has been achieved in the past decade and we would judge the risk as very low.

Eurozone breakup

With the impending British vote on membership of the EU, a decision to exit may result in other countries seeking to limit the oversight from Brussels. The monetary union itself may come under pressure. This would take an extraordinary effort and time to unwind, with Europe likely to be seen as a marginal investment case. Most of the pain would be in government bond markets with the corporate sector less affected. While many members of the EU are struggling with the restraints imposed, these are largely political. From a monetary point of view, many countries would probably do more damage to their economies by leaving compared to the cost of staying. In particular, their funding costs are likely to rise sharply and sources of capital would be limited.

Political instability

We can add little value here. The observation can be made that much of the political landscape is unattractive and therefore restricts corporate investment and household spending. Naturally, conflict is very unhelpful.

-

Global Equities

Over the past three years investment performance from global equities has been concentrated in four sectors – consumer discretionary, consumer staples, information technology and healthcare – each of which have achieved annual double digit returns. Unsurprisingly, fund portfolios have become skewed to these sectors to avoid relative underperformance. From a country perspective, while there have been occasional forays into non-US markets, excess returns have been more persistent in the S&P 500 and most fund managers have therefore stayed close to the regional index weights.

In the first quarter of 2016, however, rotation to some of the weak sectors of 2016 has taken the gloss off the strong performance of growth-oriented managers. On a country level, while the S&P 500 has outperformed most other regions, in recent months the currency has moved against the net outcome for unhedged Australian investors.

The question arises whether portfolios are excessively skewed to US$ growth style investment strategies. The decision rests on two criteria:

· Do US companies have earnings growth to support their selection compared to other regions?

· Are there sectors or regions where undervaluation is excessive?

The base case is the structure of the global equity market as shown below.

MSCI Sector Weights

Source: Bloomberg, Escala Partners

At a headline level, the S&P 500 is expected to show no earnings increase this year. However, this is largely due to the impact of energy sector and to some extent, financials. Nonetheless, the pace of improvement in operating earnings in the US is weakening and the quality of overall earnings is judged as poor. The evidence for this is taken as the difference between GAAP (generally accepted accounting practice)accounting standard earnings and those reported by companies. The most common issues here are the treatment of ‘exceptional’ items and accounting for stock options. In short, it implies the cash flow/share of many companies is not as strong as their headline would suggest.

A further measure that is often highlighted is the share of corporate profits compared to wages as a percentage of GDP. While there are structural features that challenge an over-simplistic interpretation of the data, such as the growth of internet and digital company profits mostly unrelated to US GDP, there is the inescapable conclusion that wage share is low by historic standards. There are bigger issues that are not discussed here. Globalisation of wages, corporate tax management, lower interest rates, government assumption of pension and welfare costs (as opposed to corporations), growth in service sectors, trend to part time jobs, have all been factors in the change in this fall in wage/GDP across the globe. Nonetheless, higher wages share is likely, at least in the short term, to crimp profit margins in the US.

Corporate Profit Share of GDP

Other regions have their own issues. Europe appeared to be on the cusp of an earnings recovery. Yet impairments in the financial sector and persistent earnings downgrades have taken the gloss off a profit flow through from the improvement in GDP. Nonetheless, there are companies that attract investors without having to make a regional call. For example, the healthcare sector is particularly fertile ground for global managers and is trading at a moderate valuation.

Another attractive feature is Europe’s better dividend yield than the US and lower use of buybacks.

Relative Value of Healthcare

Source: Deutsche Bank

Japan has been a disappointment, with the inability of structural reforms to gain ground and the stronger Yen a major headwind to the export sector. While there are pockets of interest, most fund managers have reduced their holdings.

Emerging markets have been the best performer this calendar year. The cause has been a combination of stability in China, narrowing current accounts, reduced capital flows, the decline in the US$ and subsequent rally in resources and most importantly, undervaluation. At this time it is expected to sustain some of the momentum, but can give up gains on skittish investor attitudes.

In summary, we do not believe there should be a distinct regional bias at present. The typical allocation to the US market remains close to the index, that is roughly 50%. US$ exposure can be higher if the fund is invested through ADRs (American Depositary Receipts) where the security is US$ denominated even though the registration domain is elsewhere. In our view, the most important question is the weight in emerging markets. This decision rests on the overall portfolio risk profile and time frame. The correlation with the A$ and the ASX 200 tends to be higher than other equity regions in part due to commodity and financial sector bias.

The greatest risk in relative performance at this time is a shift toward value style investing versus growth. Value is defined as low P/E, low P/Book, higher yield etc. Growth is based on EPS growth, higher Price to Growth and higher ROE. In financial markets, this debate is likely to bypass most investors, but is considered one of the key features in equities. Value generally performs well out of a downturn as stocks are oversold. As earnings growth returns and momentum picks up, this then becomes the predominant style. Once the sense is that the earning cycle is maturing, funds then return to stocks left behind or out of favour for a range of reasons. Below is a representation of the typical factor styles and their relative performance against the index. Long term value is a better performer than other factors. However from 2007, growth predominated.

Source: Deutsche Bank

The first quarter of this year has changed the pattern. Energy, utilities and telco stocks have outperformed the previous favourites and the question is whether there should be a greater allocation to so called value managers. We are reluctant to increase the recommended allocation given the nature of this economic cycle. Nonetheless, the diversity of managers we recommend will provide some holdings in value stocks.

-

Fixed Income

The sceptics might think that diversification within an asset class is just a way of always having a winner in the pack. However, avoiding concentration risk in a fixed income portfolio is not a matter of randomly casting the net wide, but instead is used on a number of different levels within portfolio construction to firstly preserve capital and secondly to enhance returns.

From a macro perspective this includes assessing:

· Long interest rate duration (fixed rate) vs short interest rate duration (floating rate)

· Government bonds vs credit bonds

· Domestic bonds vs offshore

Then from a micro level ensuring:

Diversification across sectors and individual issuers

Long Duration versus Short Duration

The long term trend of declining global interest rates has resulted in a 34 year bull market for long duration bonds, outstripping the performance of their floating rate equivalent. In this time frame, the best trade would have been to only invest in fixed rate (long duration) bonds as opposed to short duration products (for example floating rate notes and short dated bonds).

Source: Bloomberg, Escala Partners

However, as with all disclaimers, ‘past performance is not an indication of future performance’ and there are new forces at play that undermine the likelihood of this being repeated.

In favour of long duration bonds, is the quantitative easing in the EU and Japan, falling rates on a global scale (with 25% of the global bond market now in negative territory) and low expectations for growth and inflation. In the other camp (favouring short duration bonds) there is the assumption that the rate cycle no longer has firepower and the Federal Reserve bank is embarking on their ‘normalisation policy’, albeit slowly. The degree of issuance by both governments and the corporate sector add another level of complication.

Further to this, there have been changes in the liquidity of these instruments, as bank balance sheets shrink, which should translate to a steeper rates curve as liquidity premiums for longer tenor are priced in. If one has the view that this is already accounted for, then long duration bonds may offer attractive returns from ‘rolling down the curve’. Alternatively, if there is a liquidity shock yet to come, the result may well be volatile bond prices.

With all of these factors in mind, we expect the rates curve to remain range bound in 2016 and there is value in incorporating both long and short duration bonds into the asset allocation. Our current recommendation is to include 40-50% in long duration (4-6 years) to achieve capital protection in the event of a downturn, with the remainder having interest rate exposure under 1 year where credit yields will form most of the return.

Credit versus Government Bonds

The long term correlations between credit (spread product) and government bonds are negative, however, more recently this relationship appears to be breaking down as correlations have converged. The chart below depicts the performance results for two indices representing treasuries and corporate bonds. While an allocation to both would have smoothed out returns from 2001-2013, the last 3 years have bucked the trend as prices have moved in the same direction.

Performance of Global Credit vs Global Treasuries 2001-2016

Source: Bloomberg, Escala Partners

Adding a further layer to this, credit is often positively correlated with the equity markets reinforcing the need to diversify from this segment.

While the performance results of credit and government bonds have been very similar in the last 3 years, the rationale for these results has been very different. In first quarter of 2016, global government bonds performed well as US bonds rallied following dovish comments by the Fed, while European bonds were supported by further quantitative easing by the ECB.

Domestically, government bonds had a strong start to the year before retracing some of these gains in March as the market wound back the probability of further rate cuts by the RBA.

In credit, spreads widened in both investment grade and high yield markets (prices fell) as equities tumbled in the first 6 weeks of this year. A change in sentiment towards risk assets resulted in spreads contracting from mid-February onwards, with corporate bonds rallying significantly.

These very different drivers of performance cement the need to have exposure to both credit and government bonds as we expect credit spreads to remain volatile and central banks active. At the beginning of the year we increased our allocation to Australian government bonds through the use of the Jamieson Coote Bond Fund and Henderson Fixed Interest Fund with a continued recommendation of exposure to global sovereign debt through the Franklin Templeton Global Aggregate Bond fund and the Legg Mason Brandywine fund. This view remains unchanged.

We are constructive on credit, and despite some recent contraction in credit spreads, this sector still looks attractive relative to historic levels (bar 2008/09). We do however expect default rates to increase in the high yield market which is likely to have short term negative implications for all credit products. However, for investment grade credit this is likely to be a temporary aberration, and for high yield the inflated coupons should be sufficient to buffer adverse periods, as long as there are no direct defaults in the portfolio. We use hybrids, Kapstream Absolute Return and Macquarie Income Opportunities fund to gain exposure to credit. Franklin Templeton Global Aggregate Bond fund and JPM Global Strategic bond also have credit allocations.

Credit Spreads

Source: JP Morgan Asset Management

Domestic Bonds versus Offshore

The advantages of investing offshore is the access to a much deeper and more liquid bond market. Recently we have seen the economic growth disparity between different regions and the divergence in their economies and monetary policies.

A global reach opens up opportunities for investors to take advantage of the different bond market cycles. As vindication, in the past 10 years global government bonds have outperformed domestic bonds by up to 4.9%p.a., while the local index has outperformed global by 2.8%p.a. The chart below shows the correlation of government bonds in the US and Germany, illustrating the divergence in opportunities.

Source: JP Morgan Asset Management

Despite global fixed income funds being fully hedged, there may be potential cashflow implications if there are large moves in currency positions. This can result in irregular distributions (added value instead reflected in the unit price). Additionally, we recognize the comfort of having a home bias and the benefits of the regular distributions from domestic funds, TD’s and hybrid securities. Our current weighting is 30-50% to global funds with the remainder in domestic funds and securities.

Diversification across sectors and issuers

Winners and losers within fixed income rotate. There is no secret recipe for picking which sector is going to be next on the leader board and which will get the wooden spoon. This is consistent with our recommendation of using a mix of managed funds, each with different strategies and sector exposure.

The following table identifies sector returns for fixed income in the last 10 years based on US data. ‘Asset allocation’ is illustrative of a blended mix rather than our recommendation.

Fixed Income Sector Returns

JP Morgan Asset Management

Perhaps the most important part of a fixed income investment is security selection. Defaults will be the biggest drag on performance. This is why it is so important to invest in a pool of fixed income bonds with limited concentration risk to one issuer which is achieved through a manger given minimum parcel size. The managed funds that we use all have tight risk controls and the majority have in excess of 100 issuers in the fund.

-

Australian Equities

More so than in other developed markets, the Australian equity market is exposed to a higher level of concentration risk among individual stocks. The most obvious of these is by sector, although risks that are less visible to the casual observer include those related to particular market themes and cyclical factors (such as interest rates, currency and commodity prices) as well as risks associated with company size.

Sector concentration: resources and financials

Historically, Australia’s equity market has been dominated by two sectors: financials and resources. It follows that direct Australian equity portfolios have typically been built around these two sectors, with it not uncommon to see core holdings that include the four major banks, BHP Billiton and then one or both of Rio Tinto and Woodside Petroleum.

Perhaps more by luck than design, a portfolio strategy that has revolved around these particular stocks has performed relatively well over a long time period. In favour of the strategy is that the two groups have a low correlation; the banks, to a degree, are a barometer for the health of the domestic economy, while resources are influenced by global economic conditions and the commodity cycle.

However, longer-term themes have played a more important role in the capital growth across the sectors over the last two decades. In the case of the banks, it has been a combination of a prolonged period of uninterrupted domestic economic growth, coupled with a household sector (and to a lesser extent, the corporate sector) that has been given the capacity to take on increasing levels of debt through the gradual decline in interest rates. Exposed to the same factors, the banks have unsurprisingly moved in sync with one another (particularly when shorter time frames are considered), although investors could have still generated a better outcome through considered stock selection (e.g. Commonwealth Bank over National Australia Bank).

We note, however, that the outlook going forward is less clear. An increasing regulatory burden, limited cost-out opportunities and the potential for bad debts to normalise, has led to an expectation for lower earnings growth in the medium term. The sector screens as good value based on historic P/E bands and dividend yields, although we would argue that the environment has changed and returns harder to generate given capital requirements. We therefore reiterate our view that bank weightings should be carefully considered.

ASX 200 Banks and Resources: Rolling 12 Month Returns

Source: Iress, Escala Partners

Concentration in resources stocks can also pose problems for investors. Changes in commodity prices are the primary driver of earnings and share prices for this group of stocks. While specific commodity prices are determined by the supply and demand balance in the market, many commodity prices do still tend to move in the same direction. Global economic demand and the resources investment cycle are the overarching determinants of commodity prices and have resulted in large share price volatility in the past 10 years.

The investment case for participation in the increasing demand for commodities from developing economies remains, however is weaker than before, with supply now balanced with demand. Hence, the super profits generated by these companies is unlikely to return in the medium term. The composition of China’s economic growth is instructive, as it moves from commodity-intensive infrastructure investment spending, to an economy more driven by the consumer. This transition may be better played through consumer-focused stocks, whether they be global in nature or country-specific. Our global fund selections have a bias to this theme.

Capitalisation bias

A further risk that many passive portfolios may exhibit is a bias to large capitalisation equities. With the top ten stocks in the Australian market accounting for close to half of the overall index, the market returns are often dictated by the performance of this group. However, the last 12 months has provided solid evidence illustrating why investors should broaden their equity investment portfolios beyond large capitalisation stocks.

While ASX 20 stocks are typically market leaders, many are quite mature businesses that are now of a size where their natural rate of revenue and earnings growth is low. Australia’s small relative size and isolation from the world has ensured a high number of oligopolies, however these too can be targeted over time. For example, the major supermarket chains and department stores have faced market share and margin pressure from international interlopers, while Telstra has been undermined by smaller, more nimble telcos.

Interest rate risk

Investors also need to be conscious of specific risks that can affect a broad range of companies across the market. Interest rate movements affect all companies to a certain degree, although there are some parts of the market that have a high correlation. Companies that are typically most affected are defensive sectors that can support higher leverage (e.g. infrastructure, utilities, REITs), which are the biggest beneficiaries as interest rates fall. The compression in long-term bond yields over the last decade has been a significant tailwind for these sectors.

High yielding equities can also be driven by changes in interest rates (and there is a natural overlap between these stocks and the defensive sectors described above). This influence is greater in the global low rate environment, where income seekers from other asset classes have bought equities for yield, despite the higher risks associated with capital values. This factor has been a significant driver of the convergence in dividend yields across sectors, with most ‘high yielding’ sectors now offering only a slight dividend premium to the market.

While the positive correlation between high yielding equities was a key driver the market’s performance from 2012 to early 2015, this relationship has broken down to a degree in the last 12 months following the decline in the dividend yield premium. A greater focus on the underlying earnings drivers of the major banks and Telstra has seen these companies perform poorly over the last year, while the capacity for improving earnings and/or distributions has led to the continued outperformance of utilities, REITs and infrastructure stocks.

Interest rates also have an impact on the valuation of more growth-orientated companies. A lower discount rate for cash flows can boost the net present value of longer-dated earnings. The critical question here, however, is why interest rates are low. If it is a result of lower economic growth and inflation expectations (as is the principal reason in the current environment), then the resulting downward adjustments to earnings expectations will generally offset the benefit. The ‘sweet spot’ for growth companies in a low growth/low interest rate setting is those that are less affected by general economic conditions and instead have structural tailwinds that will persist regardless.

Currencies

Currency markets are another important driver that can have a large bearing on the performance of stocks across the market. The volatility of the Australian dollar means that the currency outcome is often much less predictable than the underlying earnings of these companies, which span many sectors of the market. These include industrials (Brambles, Amcor), building materials (James Hardie), financials (QBE and Macquarie), healthcare (Cochlear, CSL and Resmed) and REITs (Westfield). Most of the companies in this group have posted respectable underlying earnings over the last few years, however returns have been enhanced by a tailwind of a weaker Australian dollar.

Renewed strength in the dollar has recently altered the outlook for the domestic investor for this group, and with the dollar returning to close to what many would view as fair value, actual underlying earnings figures should be the focus.

Growth versus value

Finally, the question of whether an investor’s portfolio is tilted more towards ‘value’ (low earnings and P/E valuation) or ‘growth’ (high earnings growth expectations) companies will generally be influenced by their investment objectives. Nonetheless, these two broad groups can show quite different performance compared to benchmark indexes in any given time period, and the stocks within each may trend in the same direction. A portfolio that is thus weighted towards either group may be exposed to concentration risks that are separate to those described above.

Presently, the group of companies exhibiting reasonable earnings growth in the market is narrow, and as we have highlighted recently, the market has now applied a higher premium on these stocks compared to historically. Stocks delivering on high expectations have been rerated, however it follows that the risk from companies disappointing is elevated. While growth has outperformed value for a number of years now, this trend has reversed in early 2016. Resources, which would have once been labelled as ‘growth’ on the expectation of sustained strength in commodity prices and demand, are now listed as ‘value’ by some.

Conclusion

In summary, we encourage investors to strike an appropriate balance in their Australian direct equity portfolios and ensure that risks are mitigated through an appropriate level of diversification. Diversification is not just achieved by adding additional stocks to a portfolio, particularly if the drivers of earnings and share prices are similar. This is important in the current equities environment, where earnings growth has typically been slow, but steady and where valuations have ventured into the upper end of fair value.

-

Alternatives

As we have recently provided a paper on alternatives, we will briefly summarise a few points relevant to the question of concentration.

An important part of our selection of recommended funds was to provide a different aspect to the management of investment assets. This may be in the approach. For example, market neutral funds are in equities but can be totally uncorrelated to the performance of the market overall. Other such as debt funds participate in sectors where typically investors do not have exposure, such as mortgage backed securities.

We have noted which alternative strategies are a substitute within an asset allocation (for example long short funds) or at least the weight towards the asset class that comprises the alternative should be taken into account.

As the most common approach to equity is so called bottom up, that is picking stocks rather than judging the direction of the market and credit managers focus on the credit quality of a portfolio, a macro strategy that does take the economic relationships into account can perform very differently to the asset specfic fund managers.

Alternative funds are perhaps the best way to avoid concentration of themes in a portfolio.