-

Overview

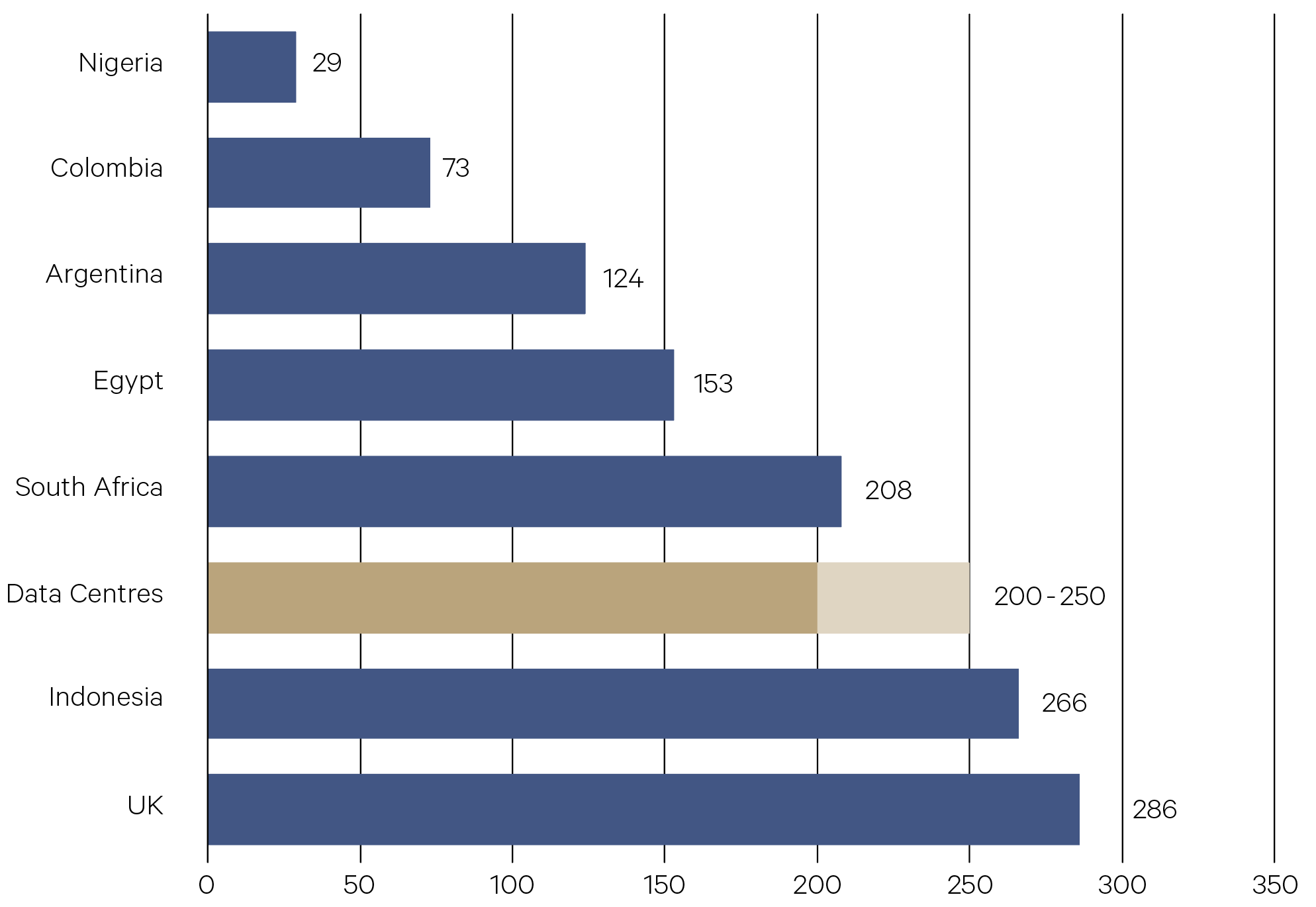

Artificial intelligence is set to define the investment landscape of the early 21st century, but this technological revolution requires substantial energy and infrastructure. Data centres – dedicated servers for AI and cloud storage – consume vast amounts of electricity to power and cool their systems, with a single hyperscale centre drawing up to 1,200MWh per day – enough to boil a kettle 12 million times.

Forecasts from the U.S. Department of Energy indicate that data centres will consume around 12% of annual electricity consumption in the U.S. by 2028. Meeting this demand has led to a revived interest in nuclear power, a technology that peaked in the late 20th century but has since been overshadowed by concerns around safety.

Data centre energy consumption in 2020 (TWh)

Source: World Bank, IEA

—

Building advanced AI systems will take city-sized amounts of power.

Source: White House brief

—

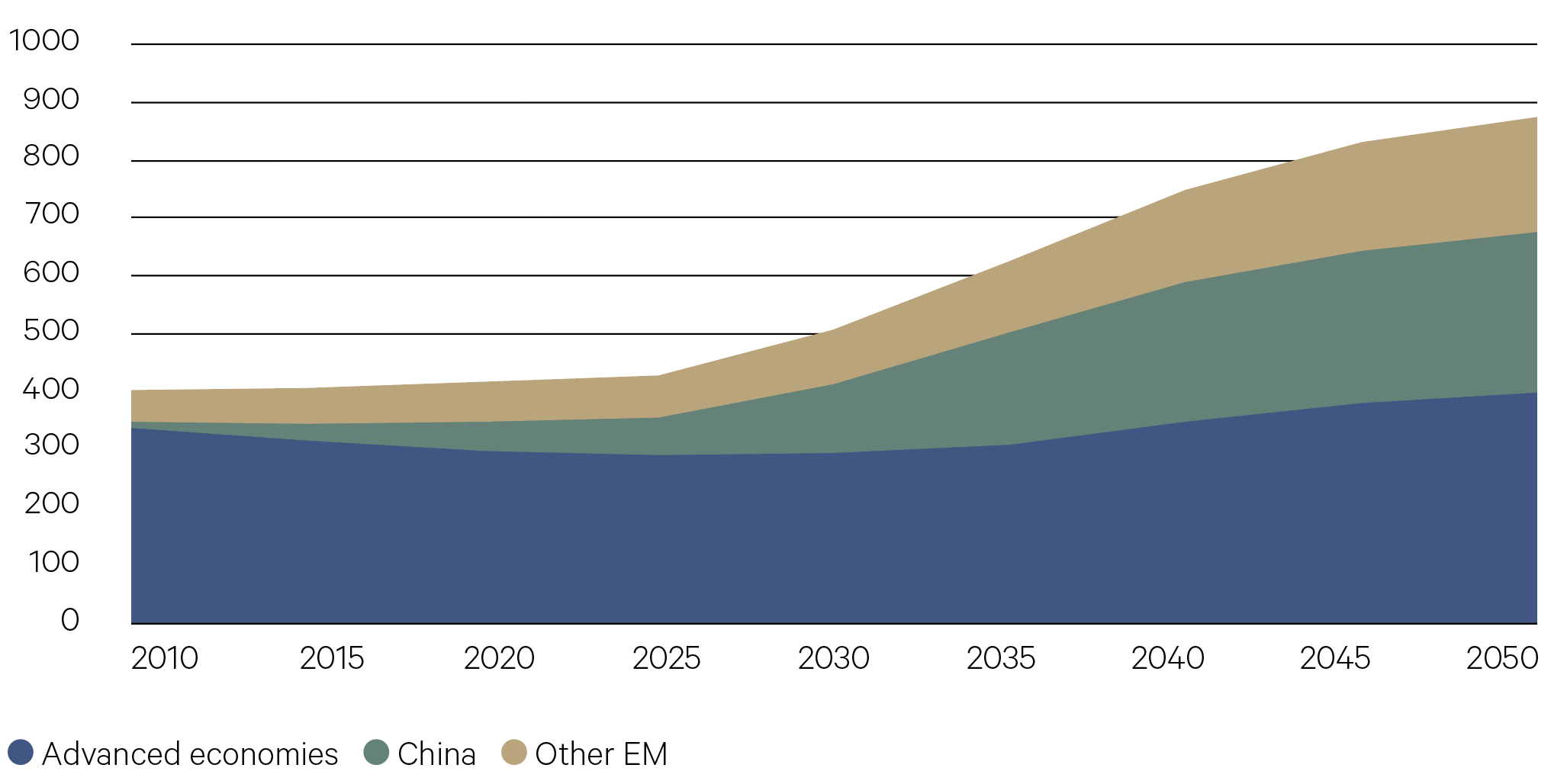

Data centres consumed around 415TWh in 2024 – about 1.5% of global consumption – a figure projected to more than double by 2030. Tech giants, such as Meta, Amazon and Alphabet, are signing long–term nuclear power purchase agreements to secure the energy needed for hyperscale AI operations. At COP29, 31 nations pledged to triple nuclear capacity by 2050, and in the U.S., executive orders aim to fast track licensing to 18 months and quadruple nuclear generation in the next 25 years.

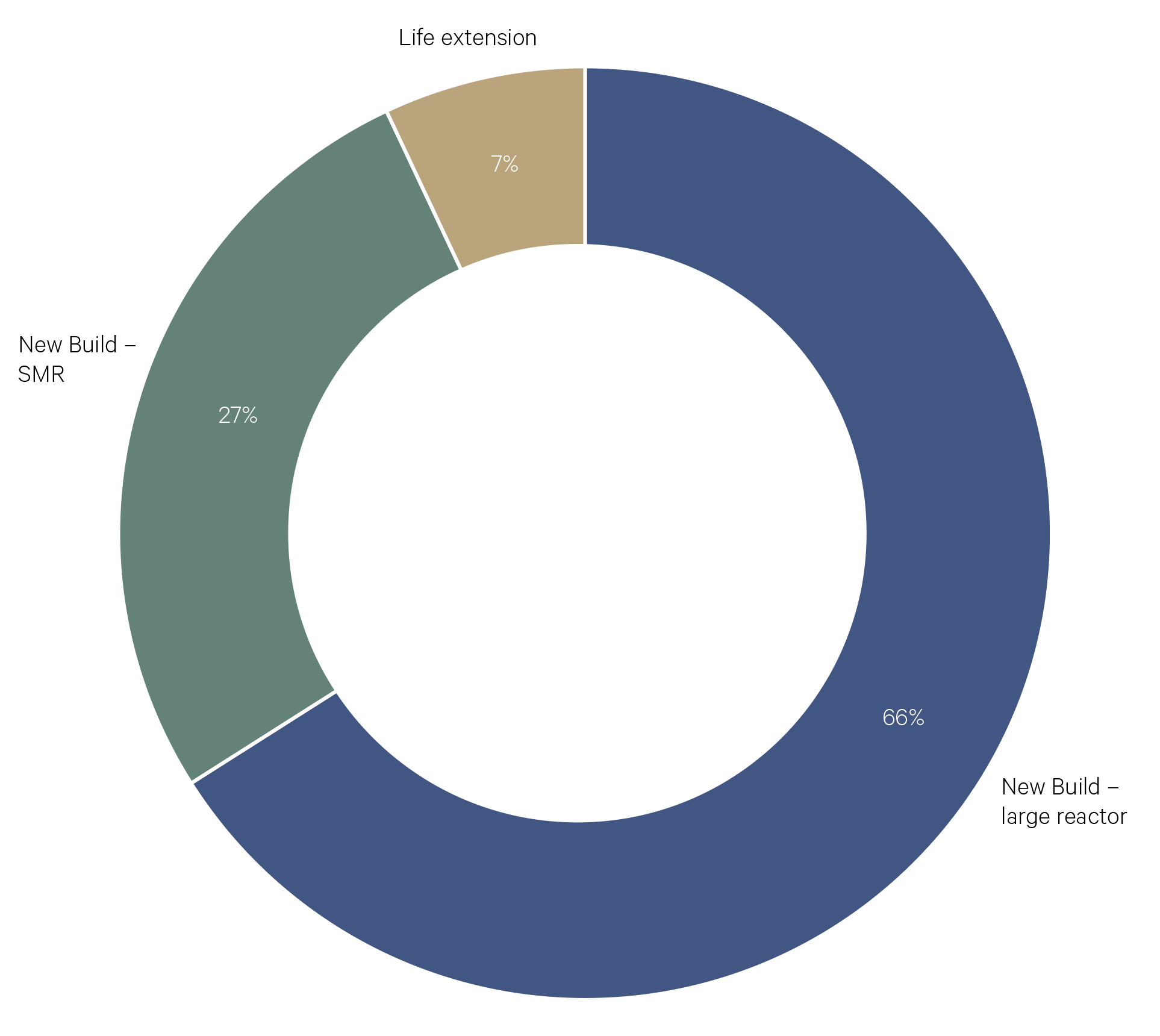

Globally, 61 reactors are currently under construction, representing more than 70GW of new capacity – enough to power the whole of France. Small Modular Reactors (SMRs) are at the heart of the nuclear renaissance representing 27% of all new investment in nuclear over the next 25 years. These factory–built units promise shorter construction times, enhanced safety and lower cost than traditional large reactors.

Currently, only two SMRs are licensed, approved and operating, while one reactor is in the testing phase. SMRs offer faster construction times, around 3–5 years versus around ten for traditional reactors. Power production is anticipated to be around half the cost. Once designs are standardised, components can be mass manufactured and shipped to site.

Reactors can be co–located with data centres, or on repurposed coal production sites, utilising existing grid connections. The modularised designs aim for improved safety with fewer failure points, and longer periods before refuelling, limiting the movement of radioactive components.

For investors, SMRs offer shorter investment timelines at around 20 years to breakeven on a conservative estimate, versus up to 30 years for traditional reactors.

Nuclear capacity by region (GW)

Source: IEA, forecast from 2024

—

31 – Nations pledged to triple nuclear capacity by 2050

Source: IEA

—

How global investment in nuclear energy is expected to be allocated, 2024–2050

Source: IEA – Announced Pledges Scenario

There are multiple entry points for investment in nuclear energy. In equities, there are opportunities at all levels of the supply chain from uranium mining and enrichment, reactor design and construction, to utilities providers who own and operate plants. In fixed income, green bonds with nuclear exposure are an avenue for investors concerned about responsible investment, with nuclear classed as a clean energy with no direct carbon emissions.

In alternatives, investors can be exposed to the design and development of SMRs through venture capital investing, as well as the construction of reactors through infrastructure investing. With up to US$3 trillion forecast for investment in nuclear over the coming 25 years, the nuclear renaissance is an investment theme that will continue over the coming decades.