-

Overview

The era of stability that defined much of the 21st century was built on a powerful illusion – the belief that the global economy could generate prosperity without sacrifice: governments could spend freely, companies could borrow cheaply, households could consume endlessly, and geopolitical stability could simply be assumed.

In truth, it was a “bonfire of the vanities”: a collective conviction that abundance could be created and consumed without cost, even as inequality grew beneath it like kindling. The widening gap between winners and losers of globalisation created the ideal conditions for a political firestorm.

That illusion is gone. The fire now flickers across many countries, destabilising political systems, causing economic disruption and creating dispersion of returns for investors. Donald Trump’s return to the White House wasn’t the catalyst, but it has been an accelerant. His move on Venezuela is the most recent example of that.

—

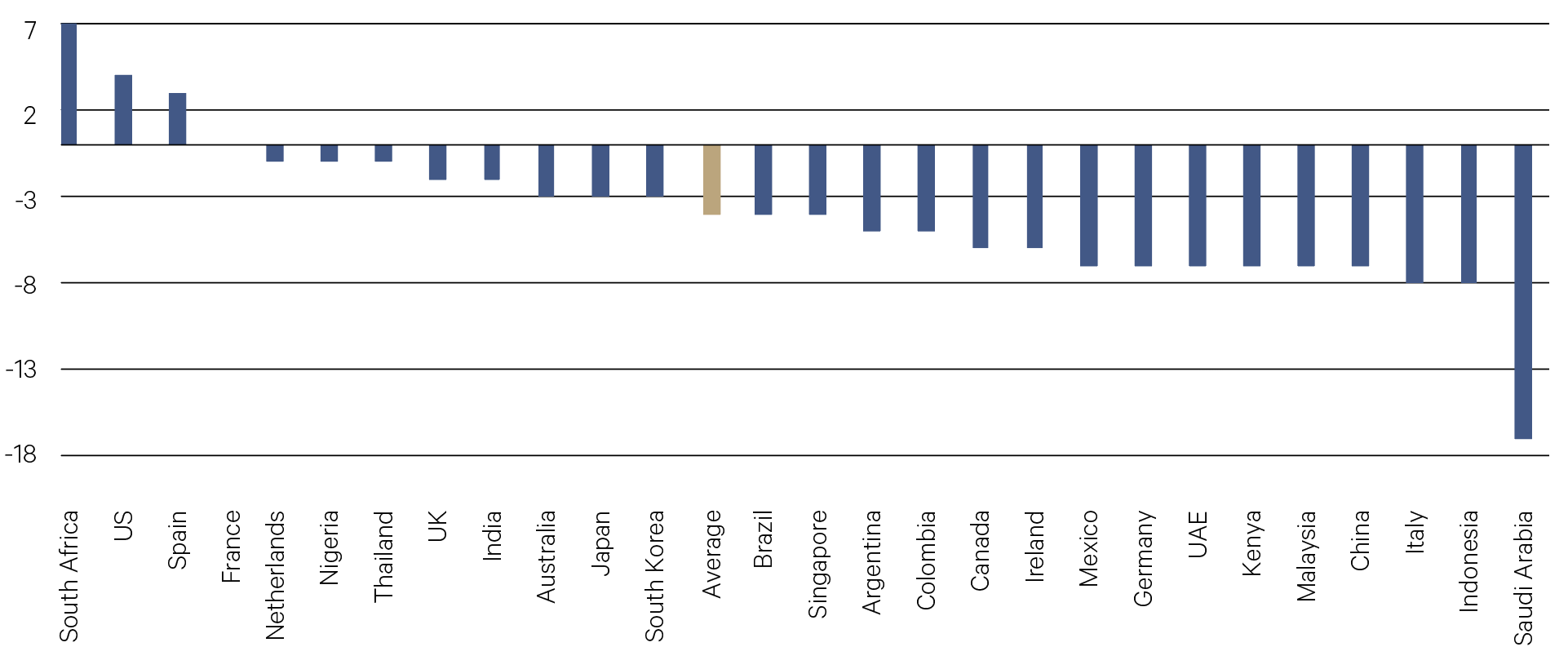

23 – The number of countries out of 27 that registered a decline in trust in the UN.

Source: Edelman Trust Barometer, 2024

—

When the kindling is lit, the bonfire becomes destabilised

The easy option to addressing inequality is entitlement–driven fiscal models. But with debt levels already elevated, the scope for painless solutions is narrow. Structural reform is harder to deliver in an environment of depleted political capital.

This was evident through the “ super–election” year of 2024 and the elections that followed in 2025.

Across countries, leaders faced electorates that were polarised, distrustful, and unwilling to accept austerity or long–term reform. The rise of coalition governments and fragmented mandates has slowed decision–making and weakened policy consistency.

The resulting pattern that is now emerging is:

- declining trust in institutions

- shrinking political mandates

- persistent fiscal strain

- rising geopolitical insecurity, and

- growing voter discontent.

—

7 – The number of French prime ministers under Macron’s recent leadership.

Source: Foreign Affairs Review

—

When the structure is destabilised, trust wanes — disruption follows

Gold above US$5,000 per ounce is no longer about inflation protection. It is the market signalling a loss of trust in the political management of money and in the institutions that underpin it.

The erosion of trust generally has become a direct source of disruption. Post–pandemic scepticism toward China disrupted global supply chains. Distrust of expertise and institutions complicated the execution of climate and clean–energy policy. Suspicion of trading partners drove the sharpest escalation in tariffs since the 1930s. Distrust of immigration produced the most restrictive border policies since the 1950s. And waning trust between allies weakened multilateral agreements that once supported global coordination.

Gold (US$ per ounce)

Source: Bloomberg as at 28/01/26

—

20 – The dispersion of equity returns last year was the widest in 20 years.

Source: Bloomberg

—

A destabilised, disrupted world is a world where the dispersion of outcomes rises.

Countries have responded very differently to these disruptions.

The U.S. has turned to tariffs and industrial subsidies, China to self-sufficiency and state control. Germany has favoured cautious de–risking, while France has pushed strategic autonomy. Japan has prioritised supply-chain security, Australia resource security.

Defence policy dispersion is clear – Germany and Poland are accelerating, Japan is responding to immediate China-related risks, France is more measured given existing capability, and Italy and Spain remain constrained by fiscal limits, and for Spain, distance to the Russian threat.

Policy is now national – shaped by domestic politics, fiscal capacity, and strategic exposure rather than coordinated frameworks.

The result is a landscape in which outcomes differ sharply across countries, sectors, and asset classes. The best performing stock in the best performing market in 2025 was Dongyang Express. This is not an AI stock. It is not listed on the Nasdaq. It is a Korean logistics company that benefited from the policies of its government to re–industrialise and localise supply chains.

Change in net trust in the UN, 2022-25 (%)

Source: Edelman Trust Barometer

Who benefits in 2026?

a. Investors who are more refined risk takers

The world of 2026 is meaningfully less U.S.–centric than the world of the past 30 years, but not because the United States has suddenly become irrelevant. Rather, the forces shaping the global economy – political destabilisation, economic disruption, and investment dispersion – are reducing the degree to which one country sets the rhythm for everyone else. Developed markets are no longer interchangeable. Sovereign risk now shapes returns, and geographic diversification matters more than regional allocation.

b. Investors who are more active

Where passive allocates capital by size, active allocates by merit – and merit matters more when the distance between winners and losers widens.

c. Investors who invest in private markets

Destabilisation also creates uncertain outcomes that can lead to heightened volatility. Private markets can provide an attractive safe harbour in that volatility storm.

d. Investors who follow the money

Developed market governments are showing little appetite for fiscal restraint. Despite rising debt levels, high interest burdens, and fading political consensus, fiscal support is the path of least resistance.

Capital will flow toward the countries, sectors, and companies positioned to benefit from persistent fiscal accommodation.

The investment message for 2026 is clear: differentiation and fragmentation now define the shifting landscape that was the bonfire of the vanities. Returns will be driven by recognising – and pricing – those differences.