-

Overview

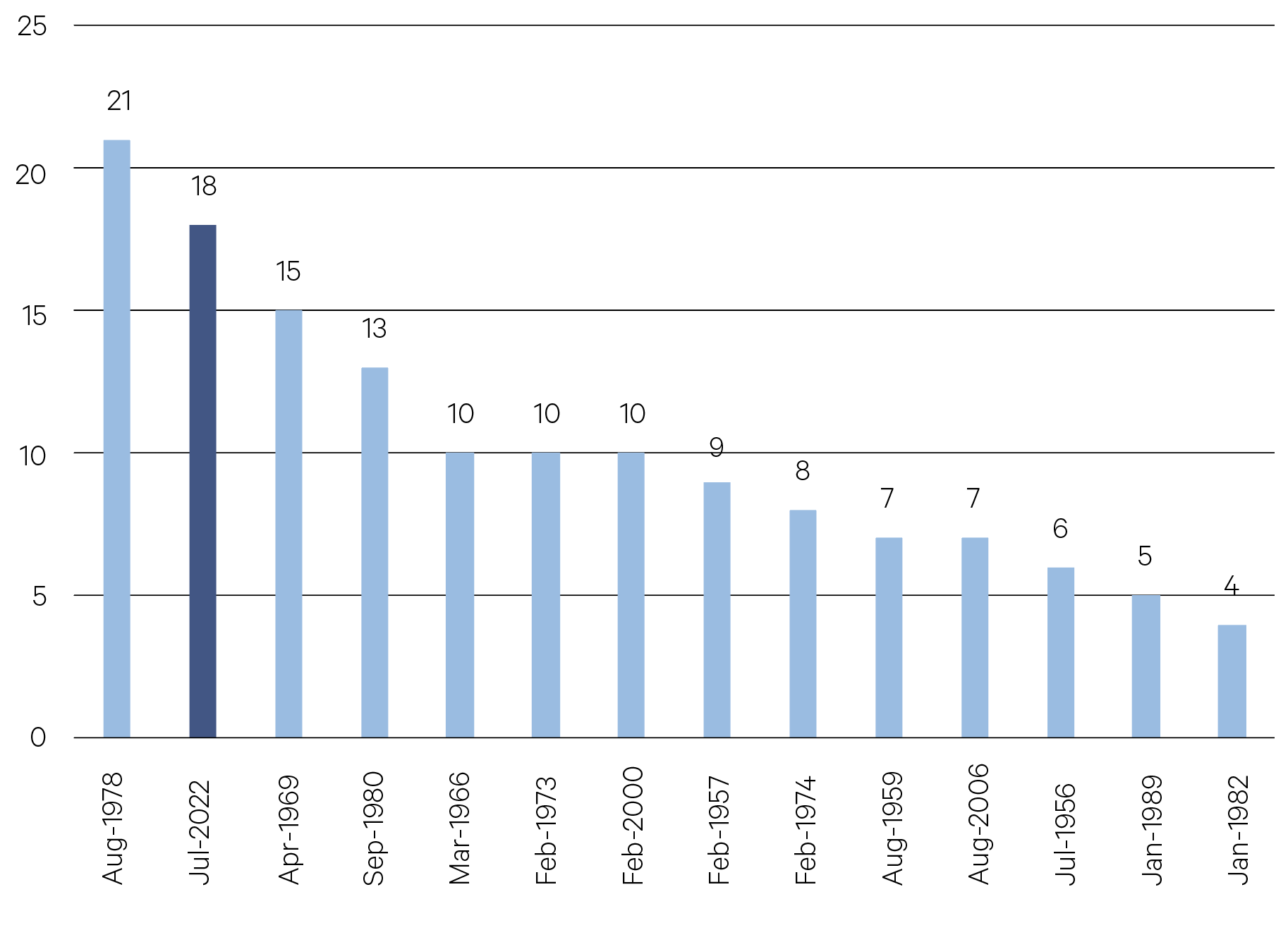

Over the past 21 months, the US has raised interest rates by five-and-a-quarter percentage points, taking the difference between short-term and longer-term interest rates to a level not seen since the 1980s. Known as an inversion, such a situation has historically spelled trouble for an economy – often foreshadowing a recession. Except for an extremely brief/mild inversion in 1998, inversions over the past six decades have had a perfect track record of signaling recessions to come. This is based on the perception that the central bank has taken policy too far into restrictive territory.

The need to raise interest rates so much reflected the fact that the U.S. economy was stubbornly immune to this tightening campaign. There are several possible reasons for this, including pent-up demand for services, strong wage growth and surplus savings. A staggered adjustment process in various interest-sensitive sectors may also have acted as a cushion that lowered the economy’s overall sensitivity to higher interest rates.

Duration of yield curve inversion (# of months)

Source: Deutsche Bank

—

525 bpts – The amount that interest rates were lifted in the last 21 months in the US.

Bloomberg

—

None of this is to say there has been a structural change in the way the economy responds to higher interest rates. It was more a reflection of the time.

It is possible then that the Federal Reserve will need to act as aggressively on the downside as these one-off factors wash out of the system. This is certainly what the bond market is pricing in – an aggressive rate cutting program beginning as early as March. Pent-up demand does seem to have been satiated, surplus savings have been spent and wage growth is now falling.

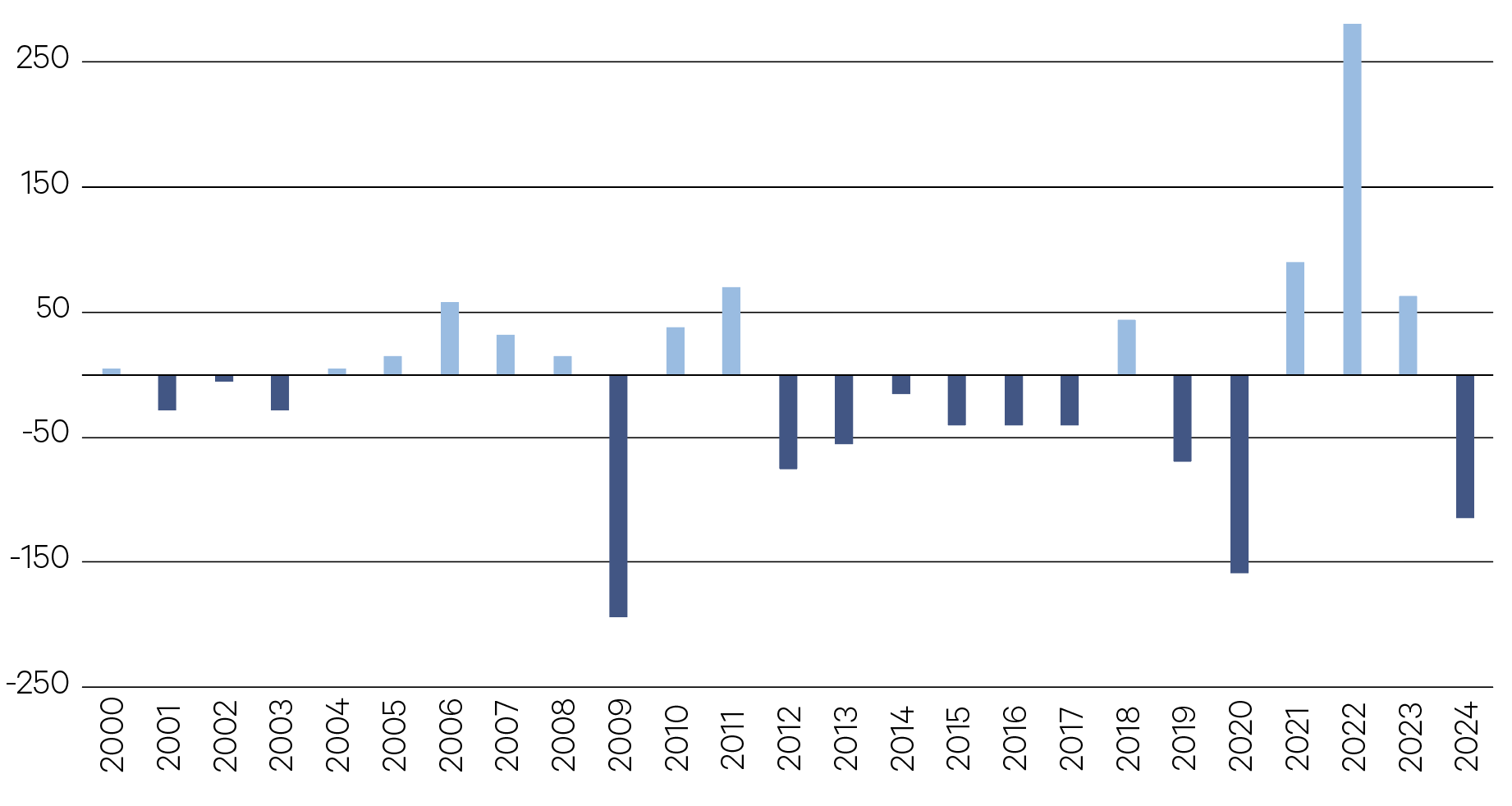

Interest rate cuts will be a theme across most markets in 2024. For the first time since 2020 we are likely to see more global rate cuts than hikes.

Global central bank rate hikes vs cuts (annual)

Source: Bank of America

—

152 – The number of rate cuts expected from global central banks in 2024.

Bank of America

—

The tightening cycle was less aggressive in Australia than in the US. This in part reflects the more interest rate sensitive nature of the Australian economy. While there was pent-up demand for services and sizeable surplus savings, wages growth didn’t hit the record highs it did in the US, despite a similarly tight labour market. The rate cutting cycle will start later in Australia than in the US.

—

425 bpts – The amount that interest rates were lifted in the last 19 months in Australia.

Bloomberg

—

Long-maturity bond yields tend to peak around the last rate hike before declining 100 basis points on average over the next year or so. This potential for capital appreciation in the price of the bond, together with the attractive starting yield, makes long-term bonds an attractive choice in 2024. We particularly prefer domestic bonds over global given the higher probability we assign to a recession in Australia.

After the curve inverts, corporate credit spreads tend to peak on average two years later. That means, if past relationships persist, we should expect to see some widening in corporate credit spreads in 2024. This, together with some rise in defaults as growth slows, makes us more cautious on corporate credit this year compared to 2023.

Credit still remains attractive from a yield perspective, however. A yield of between 8-9% for sub-investment grade provides an attractive cushion, even if spreads widen slightly. We believe that income opportunities from higher yields will generate the bulk of fixed income returns in 2024. In that context, we believe investors can meet their fixed income investment objective without taking undue credit risk.

—

US$1trn – The annual interest bill on the US$32trn US government debt load.

Bloomberg